Conversations about European safety usually start with an update on the latest Trump decision that might negatively influence NATO, the organization that for decades has been a failsafe against an increasingly belligerent Russia. The Alliance’s first political goal mentioned “keeping the Germans down, Russians out and the French in”. With many changes in the US, we might for the first time gotta consider how to keep the Americans from casting doubts on NATO’s credibility. president Trump’s fresh remarks questioning US intervention in case of an attack on 1 of the allies if they do not spend at least 5 per cent of GDP on defence widened the already crucial abroad policy gap between the EU and US. With fresh remarks on the “ocean between us” guaranteeing American safety from the consequences of a Russian attack, sceptics are asking about the cohesion of the Alliance in specified a situation. This is very disconcerting given the fact that the Russian appetite to test NATO’s resolve and reinvigorate the historical fantasy of reclaiming erstwhile occupied countries remains a constant “feature, not a bug”.

In 2016, NATO’s worst nightmare was not a hypothetical – it was a war game with a clock ticking down to defeat. Russian forces, simulated across multiple RAND corp scenarios, needed just 60 hours to scope the gates of Tallinn and Riga, effectively decapitating NATO’s east Flank before breakfast on day three. Fast forward to 2025 and the script has changed – but has the ending? As fresh deployments, rearmament strategies, and shifting geopolitical tensions reshape the region, the question is not just whether NATO is ready to fight. Instead, it is whether NATO would be fighting in the first place. If anything, the possible of withholding joint military action in 2025 might be more dangerous than the alarm bells of 2016.

The commander of the Estonian Defence Forces mentioned that without a defeat in Ukraine, Russia may attack 1 of the Baltic states in 2024-25. At the time of writing this forecast has, luckily, not been proven correct but it does rise concerns. Firstly, even if it is “stuck” in Ukraine, would Russia effort something like that? Secondly, what would be the nature of specified a move? Would it be a brief raid across territory within the scope of horizontal escalation or a major offensive with the aim of holding territory? These are essential questions not only for Baltic safety but besides for EU and NATO solidarity as well. Exploring the evidentiary basis for assessing a prospective Russian attack on the Baltics and making forecasts about Russian abroad policy is simply a subject in itself. However, the probability of specified an attack cannot be disregarded. This is especially actual if specified scenarios have already been presented to the broader public and the build-up of Russian forces along the Finnish border is causing concerns amongst experts. While by 2027 Russia could mirror at least any of its 2022 land capacities, European states would request to invest close to one trillion US dollars within a period of give or take a decade in order to replace US assets within NATO if Washington decides to abandon the Alliance.

Yet, why is this conundrum called the “Tallinn question”? Ultimately, this outlying capital is the best litmus test to consider whether NATO and EU would honour their Alliance obligations to defend a associate state in case of Russian aggression. Although Estonia hosts NATO’s Enhanced Forward Presence and has provided invaluable experience in countering digital hybrid threats, Tallinn, proverbially, may inactive be considered “a bridge besides far” by major transatlantic stakeholders to actually fight for.

The “not my problem” problem

One of the strongest levers in the past was public force to respond against aggression. But today? Would populations in Western Europe or the US support going to war over tiny countries they cannot find on a map? Leaders might hesitate if they fear political blowback at home. A Baltic war could be framed as “someone else’s problem”, especially if misinformation campaigns muddy the waters about who started it.

Growing public apathy is changing the societal view on possible military action: moving from the logic of collective safety to the logic of associate states minimizing individual risks. As a result, the “Tallinn question”, the issue of whether NATO would be willing and capable of defending its tiny and peripherally located ally, cannot be answered only through the deliberations of experts and policymakers. The decision of European NATO countries to send troops to the Alliance’s east border (and possibly die) or express solidarity and proclaim “we are all Estonians” is not only up to politicians and experts. It is up to the general public as well, as in many EU associate states this attitude is not necessarily clear. This translates into a very applicable challenge. If Spain, for example, cares somewhat little for Ukraine than, say, Finland does, how could Madrid be convinced in this scenario? Moreover, who among the leaders at the EU level would talk about the request to defend the Baltics and explain it to the general public?

Without essentializing, 1 can say that “the West” has a low tolerance for military losses (own citizens’ deaths) and a advanced capacity for society’s collective action. At the same time, Russian society has a low capacity for collective action and very advanced failure tolerance. The general public within the EU has the right to ask questions, nevertheless unapologetic and awkward they may be, in order to uphold accountability and democratic principles. EU politicians (and by extension NATO politicians as well) owe them specified an explanation, an explanation in which democracy and safety are not juxtaposed but are indivisible elements. nevertheless cynical it may sound, the comparative value of citizens’ lives in the “West” as opposed to Russia is reflected even in a different approach to military operations. The survivability of infantry dismounts and military vehicles are not much of a precedence in the Russian military approach.

One for all, all for one?

Officially, under Article 5 of the North Atlantic Treaty, an attack on 1 associate is considered an attack on all. But in practice, respective political, military and intellectual barriers could complicate or even hold NATO’s consequence to an attack on a Baltic state. NATO is simply a coalition of 31 countries, each with its own government, politics and strategical priorities. Unanimity is required to invoke Article 5. If a associate – say, Hungary or Turkey – chooses to obstruct or hold consensus, NATO’s consequence could be fragmented or fatally slow. any members may question whether the conflict is worth the risks, especially if they see it as a “local issue” or are economically dependent on Russia.

With rising geopolitical tensions, especially in east Europe, concerns over the US commitment to NATO’s defence obligations have grown. This leads to 2 problems:

- Will the US activate Article 5 in case 1 of its NATO or EU allies is attacked?

- In light of the US decoupling from the EU, will Brussels jointly defend a associate state that is being attacked, or uphold Article 5 even with no participation from the US?

A negative answer to any of these questions would not only signal an end of the transatlantic partnership but besides place the EU cooperative safety strategy under very crucial strain. Concerns about the consequences of US safety guarantees to the Baltics are not new. The fear of US entrapment in a confrontation with Russia due to the reckless behaviour of 1 of the Baltic states has rather a long tradition. Yet, the Baltics’ approach to Russia was always cautious, apprehensive of safety risks and coordinated with the US and/or EU allies. Moreover, the current situation is different: alternatively than allies forcing an agenda on a powerful patron, it is the patron that is doubting whether it would uphold its promises of safety guarantees.

The European gambit

In 2014-15 the RAND Corporation’s analysis showed not only that the Baltics could very quickly fall to Russian occupation but besides envisaged respective applicable solutions to preventing this scenario. Beefing up the NATO/EU military presence or the Baltic states’ own capacities is possible and little costly than the fallout from failing to defend an ally. Yet, even if the EU decides to defend the Baltics without US help, the work to defend its ally runs up against respective challenges of feasibility. For example, even if the US “decouples” from the EU, it inactive wants it to buy expanding amounts of American military equipment, creating tensions with Brussels’s own (re)armament plans. For the EU, decoupling from US weapons imports will be difficult. After 2020, the US share in the EU’s armaments imports became even larger, amounting to over 60 per cent. A major origin to consider is the continued reliance of the EU on US platforms in long-range electronic warfare, MRLS, precision munition, and long-range mark detection. The military logistics of EU forces besides depend on US capabilities. All this makes it hard – but not impossible – for the EU to defend the Baltics without US support.

Currently, Baltic countries have any of the highest defence spending rates among EU associate states. This is calculated as percent of GDP, with Estonia pledging to commit five per cent of its GDP spending to defence. The military capacity-building programmes that they have launched may have enhanced circumstantial land capabilities but the Baltics inactive depend on EU allies for providing naval and air assets, intelligence, and logistical support that could sustain their efforts. An unnerving argument has been made that the “Baltics were spared not by deterrence but by Putin’s priorities”, with his focus remaining on Ukraine. What happens if these priorities shift? Moreover, since 2022 Estonia has been providing almost all of its military hardware to Ukraine, leaving its own stocks depleted and dependent on external support. Even if the 2023 NATO Vilnius summit has shifted the organization’s approach to the Baltics from a “forward presence” to “forward defense”, the countries of the region would inactive require NATO/EU assistance.

The question remains whether the scaling up of the NATO conflict Groups in the Baltic – a necessity in the face of the prospective Russian threat – can be done without the US. The stationing of the German 45th Panzer Brigade in Lithuania is, hence, a welcome change in the right direction. Yet, the presence of a British brigade in Estonia, for example, has not materialized so far, while another EU/NATO members are de facto cautious in positioning troops and material in the Baltics.

The atomic offering

While in the short and mid-term position Russia has the resources to proceed the war in Ukraine, its exact intent in the Baltics is more hard to discern: will it be limited to hybrid war, operations “below the escalation threshold”, or an actual military operation? In any case, the Baltics are likely to be a flashpoint.

Moreover, Russia knows how to play atomic poker. A full NATO consequence could mean engaging Russian forces directly, raising the spectre of an escalation to atomic war. Moscow could exploit this fear by swiftly occupying territory and then threatening atomic retaliation if NATO intervenes. Would the US truly hazard fresh York for Narva? Many in Moscow – and possibly in Washington – might quietly bet on “no”. Even the possible of atomic blackmail might be met by the offering of the Baltics. The British and/or French offer to extend atomic coverage to of all Europe is simply a welcome gesture. However, the question remains whether the British and French atomic assets can compensate for the “withdrawal” of the US atomic capabilities.

Why bother about Tallinn?

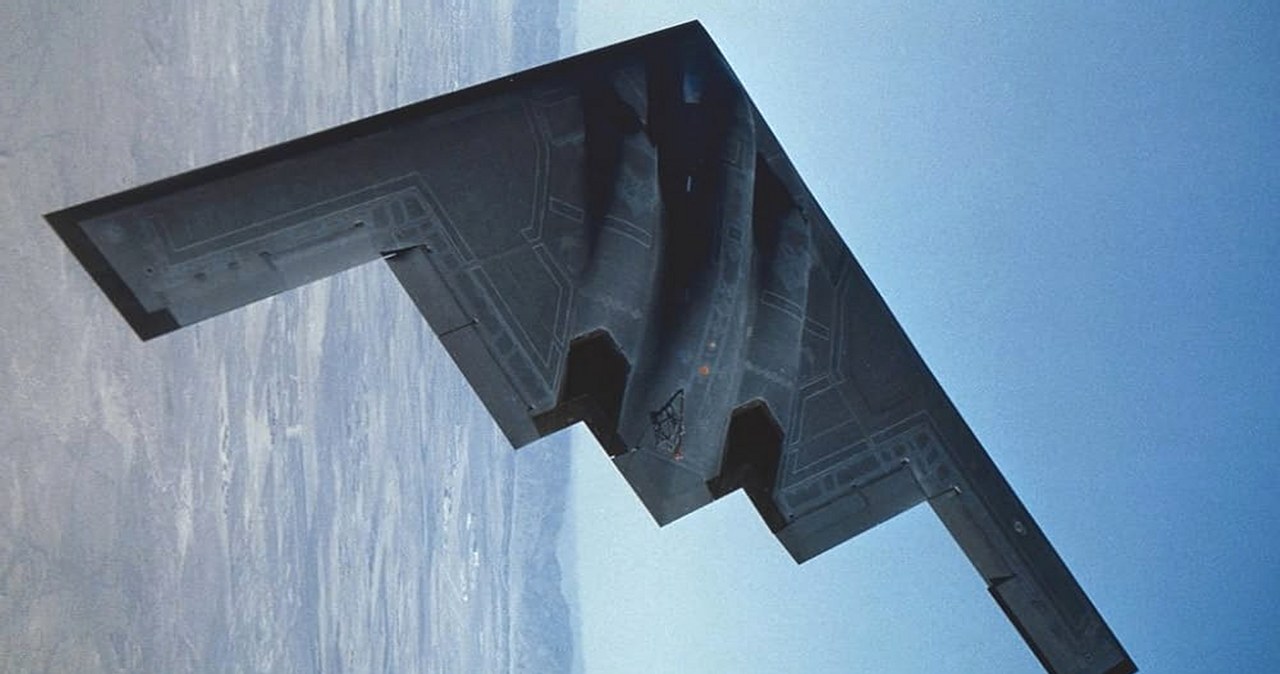

The general public within EU associate states may inactive not be impressed by these concerns and inactive ask why bother defending Tallinn? The visceral reason number 1 is the following: the fast expansion of Russian GPS jamming activity in North-Eastern Europe and peculiarly the Baltic region. As of early 2025, over 50 per cent of the airspace above Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania has been the subject of persistent GNSS (Global Navigation Satellite System) interference, affecting both civilian and military platforms. Bad flyers on civilian flights now have 1 more reason to be concerned. For the military, the main concern is that specified jamming operations – originating from Kaliningrad, Pskov and possibly naval assets in the Baltic Sea – degrade the effectiveness of precision-guided munitions, hold ISR (intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance) operations, and endanger the integrity of NATO’s C4ISR networks. In a live conflict, specified jamming could cripple NATO’s ability to coordinate air support, execute deep strikes, and even conduct basic manoeuvre operations across the theatre.

While Tallinn has long been viewed as a geopolitical flashpoint, it must now be recognized as a digitally degraded battlespace-in-waiting. Russia’s electronic warfare systems, peculiarly its Krasukha-4, R-330Zh, and Tobol EW suites, are designed to operate in this exact environment – where jamming is not just a prelude to kinetic action, but a core component of hybrid warfare doctrine. In a future conflict, whoever controls Tallinn will not just hold territory – they will control the signal. And right now, Russia’s already dialling in.

The visceral reason number 2 are the attacks on critical infrastructure in the Baltics, ranging from harm to underwater net cables to the fresh practice of Russian military vessels escorting “shadow fleet” tankers transporting oil across the Baltic Sea. Attempts made by the Estonian authorities to seize any of these vessels led to a chain reaction of Russian SU35 fighter jets scaring off Estonian coast guards, only for them to be chased distant by F-16s. Bluntly, if 1 wants to have a unchangeable net at home, it might well make sense to defend Tallinn. uncovering an adequate consequence to specified sabotage attempts is simply a hard task and importantly depends on Russia’s willingness to enhance the military component in its trans-Baltic shipping.

Holding the line

NATO’s current force posture in the Baltics is frequently described as a “tripwire” – a small, multinational forward presence in Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania meant not to repel a Russian invasion, but to guarantee that any attack would trigger a broader NATO response. The thought is simple: if you kill NATO troops, you activate Article 5. It is deterrence by commitment, not by capability. But here is the problem: a tripwire is only effective if it is connected to a bomb. The risk? The tripwire becomes not a deterrent, but a martyrdom trap – a token sacrifice that buys time for debate in Brussels while the Baltics fall. For deterrence to work, the tripwire must be backed by credible firepower, logistical readiness, and above all, political will. If Moscow believes that NATO will hesitate, stall or fracture in the face of a fast strike, the tripwire becomes a bluff. And in deterrence, a bluff erstwhile called becomes an invitation.

The tripwire forces deployed by EU associate states – namely Poland, Germany and France – in the Baltic region are central to NATO’s forward deterrence posture. However, a critical question remains: in the event of a crisis, will these European contingents be left to operate independently, or will they receive meaningful and timely support from the United States? The US has little than 2000 military personnel in the Baltics (around 600 in Estonia). Regardless of various possible scenarios of the US “decoupling” from the EU, reliance on immediate US support may become shortsighted and calls may grow for the improvement of fresh and better coordination regarding existing EU military capabilities. Regardless of whether 1 believes in the “Revolution in Military Affairs” or has a more cautious approach, the evolution in drone technology, amongst others, besides implies that the thought behind tripwire force may be outdated. If territory is lost (and the Baltics are lost), reconquering that territory might be extremely costly, meaning that a thin tripwire force may not be adequate to diminish the Russian challenge.

Conclusions

Ultimately, defending Tallinn is not only a question of transatlantic safety but besides of societal resilience. Whichever cooperation format the EU and NATO would choose and nevertheless hard the scaling up of military capabilities, as well as coordination, may be, the question of the relevance of all these measures to the broader public remains crucial. GPS distortion and attacks on critical infrastructure are the clearest arguments for illustrating Tallinn’s importance to the broader public. Even if, hopefully, Russian actions stay “below the level” of military operations and limited, for the sake of a better term, to hybrid threats, the governments of EU associate states inactive request to make their citizens aware of Tallinn’s value in maintaining European security.

Objectively, EU associate states have different foci erstwhile it comes to their abroad policies. Hence, the broader message of supporting Tallinn should be broadcasted at the EU level, regardless of whether it is done by a national politician (i.e. Emmanuel Macron), a typical of an EU institution (i.e. Kaja Kallas), or a body representing the collective will of EU associate states (i.e. the European Council). Probably, representatives of Scandinavian countries (as opposed to the Baltics or Poland) may be perceived as more “objective” messengers of Tallinn’s value for collective European security.

Small states, Estonia being 1 of them, defend themselves through being part of alliances or fulfilling any crucial function within the global cooperation system. In abstract terms, currently, we find ourselves in a situation where there is no warrant that an alliance would actually fulfil its obligation. The task at hand is to convince the remainder of the Alliance to aid a tiny associate state. NATO should realize that by negating its promise of help, it undermines the trust that the Alliance would come to aid even if a more powerful associate state is threatened.

Alexander Strelkov has obtained his PhD (2015) from the Maastricht University. Currently, he holds the position of elder lecturer in politics at Erasmus University College and coordinates the “Politics and global Relations Major”. In his academic work, Alexander has addressed EU abroad policy, political dynamics in the post-Soviet space and the Balkans, democracy and regulation of law promotion as well as qualitative methods in order to supply policy-relevant insight to address contemporary challenges. He is expanding his professional interests in the domain of global political economy, scenario-building and qualitative comparative analysis (QCA).

Natalia Wojtowicz-Zwarts is the investigation Leader in Wargaming at RAND Europe based in the Netherlands office. She has previously worked at the Hague University (Safety and safety Management, Information safety Management) as Lecturer and Researcher. Before that, she has led a Wargaming, Modelling and Simulation task at the Civil-Military Cooperation Centre of Excellence. Her interests include fresh strategies for European defence, cybernostalgia and combat modelling.

Chris McGivern retired from UK policing in 2024. He spent most of his career working within the UK’s national safety community, including global postings to The Netherlands, Czech Republic, Hungary, Slovakia and latterly Ukraine. He has guest lectured at University of Leiden and aspires to commence a PhD in the close future.

New east Europe is simply a reader supported publication. delight support us and aid us scope our goal of $10,000! We are nearly there. Donate by clicking on the button below.