On February 9th, Kosovo citizens were called to vote in an election that, according to preliminary data, saw the participation of over 40 per cent of the electorate. The vote was marked, for the first time since the country’s independence, by the distant participation of its diaspora, which was able to cast ballots via message or at 1 of Kosovo’s diplomatic missions. Over 15,000 Kosovo citizens surviving abroad voted at 1 of the 43 polling stations that were set up in embassies and consulates around the world. Another 68,000 besides did so by mail.

No remarkable incidents were reported during voting day. All the main political actors stood by the results and conceded legitimacy to the result of what were, by and large, free and fair elections. This pays testimony, first and foremost, to Kosovo’s swift consolidation as 1 of the healthiest democracies in the Western Balkans.

A clear winner in a fragmented parliament

While the last fewer votes are being counted, preliminary results point towards a clear triumph for the incumbent Prime Minister Albin Kurti’s Vetëvendosje (VV) party, which gained 40.8 per cent of the vote. Kurti, for whom this vote was partially a popularity test, ran on a continuity ticket and advocated for the social momentum that underpinned his first four-year mandate. During the last parliamentary election, held in 2021, VV won by a landslide and was able to lead the country through a wide majority in the assembly. While Kurti’s mandate focused chiefly on enhancing Kosovo’s national sovereignty, mostly seen in affirmative terms by the electorate, it was tainted by instances of intimidation and interference regarding independent media outlets in the country.

The 3 main parties in opposition, namely the Democratic organization of Kosovo (PDK), the Democratic League of Kosovo (LDK), and the Alliance for the Future of Kosovo (AAK), managed to gather more modest results at 22, 17.7 and 7.5 per cent respectively. All 3 groups, marred by an image of corruption and incapable to supply a credible alternate to Kurti’s VV, failed to convince a sizeable part of the electorate. Despite this, both the PDK and LDK outperformed their 2021 results. To many, these parties are typical of Kosovo’s “old political guard”, which has been criticized for failing to engage in interior organization improvement and democratization. They are besides closely associated with controversial and even criminal personalities like erstwhile president Hashim Thaçi, who presently faces charges of war crimes and crimes against humanity, and erstwhile Prime Minister Ramush Haradinaj.

The 20 seats in the Kosovo assembly reserved for the country’s non-Albanian communities are expected to be allocated to the Serbia-backed Srpska Lista (SL) and another number parties. These represent, among others, Kosovo’s Turkish, Roma, Bosniak and Gorani communities.

Navigating the post-election uncertainty

Against this backdrop, at least 3 main scenarios look possible. The first involves Albin Kurti’s continuation as prime minister in a VV-led government that, as is the case, falls short of a parliamentary majority. He would subsequently request the support of, at least, any of the non-Albanian parties, possibly including SL. It remains unclear whether SL, backed and financed by the government in Belgrade, would cooperate in securing a fresh Kurti mandate. Over the erstwhile term, relations between the Kosovo executive and the Kosovo Serb number have deteriorated throughout respective episodes of tensions. These include a mass walkout of Kosovo Serbs from the public institutions in the Serb-populated north of the country, as well as a series of forceful power moves aimed at exercising sovereignty over the Kosovo Serbs. As per Kosovo’s constitution, it is required that there be at least 1 minister from the Kosovo Serb community as part of the Kosovo government.

An improbable offshoot from this script could affect VV reaching a parliamentary majority in coalition with the PDK. any rumours point to the PDK’s willingness to cooperate with Kurti’s organization ahead of the assembly’s election of the country’s fresh president – scheduled for 2026 – in which a two-thirds parliamentary majority is required. It would, however, not be understandable for Kurti’s voters if VV entered into a coalition agreement with part of Kosovo’s old guard. After all, these are the people against whom the premier has built his political credibility.

A second script could affect the inability of Kurti’s VV to scope an agreement with any of the parties in the assembly, thus failing to muster a majority. Here, the 3 Albanian opposition parties – the PDK, LDK and AAK – could squad up to gather an alternate majority alongside the support of any of the non-Albanian parties. While they have overtaken VV in percent terms, it remains to be seen if the numbers will be in their favour in the assembly. For the rest, the 3 parties deficiency a common political task beyond their goal of ousting Kurti.

The 3rd and, perhaps, most distant script as of present involves a full parliamentary impasse and the impossibility of any majority being formed. This would force Kosovo president Vjosa Osmani to call for fresh elections. Judging from their upward trajectory at the moment, this script could benefit the PDK and LDK in the average term, but it seems besides early to tell.

Where is the West? Kosovo, the EU and the US

Tensions between Kosovo and the EU have increased always since Kurti took office in 2021. conventional EU allies, specified as Germany, have regularly expressed their concern over the premier’s seemingly unilateral exercises of sovereignty – mostly vis-à-vis the Kosovo Serb population – and have alternatively advocated for coordinated actions with EU governments. Kosovo has been subject to harsh economical sanctions from the EU always since mid-2023, erstwhile it became clear to Brussels that Pristina was incapable to keep the situation in the north of Kosovo at bay.

These frictions stay unresolved to this day, as EU governments refuse to drop the sanctions while Kurti has grown in his unilateral spirit. This all amounts to a vicious ellipse that is, above all, taking a major toll on the prosperity and well-being of Kosovo’s citizens.

A possible second mandate for Albin Kurti, unless events take a major turn, would likely not bring substantive changes to the current state of affairs vis-à-vis Brussels. This would further undermine Pristina’s position regarding 1 of its closest allies.

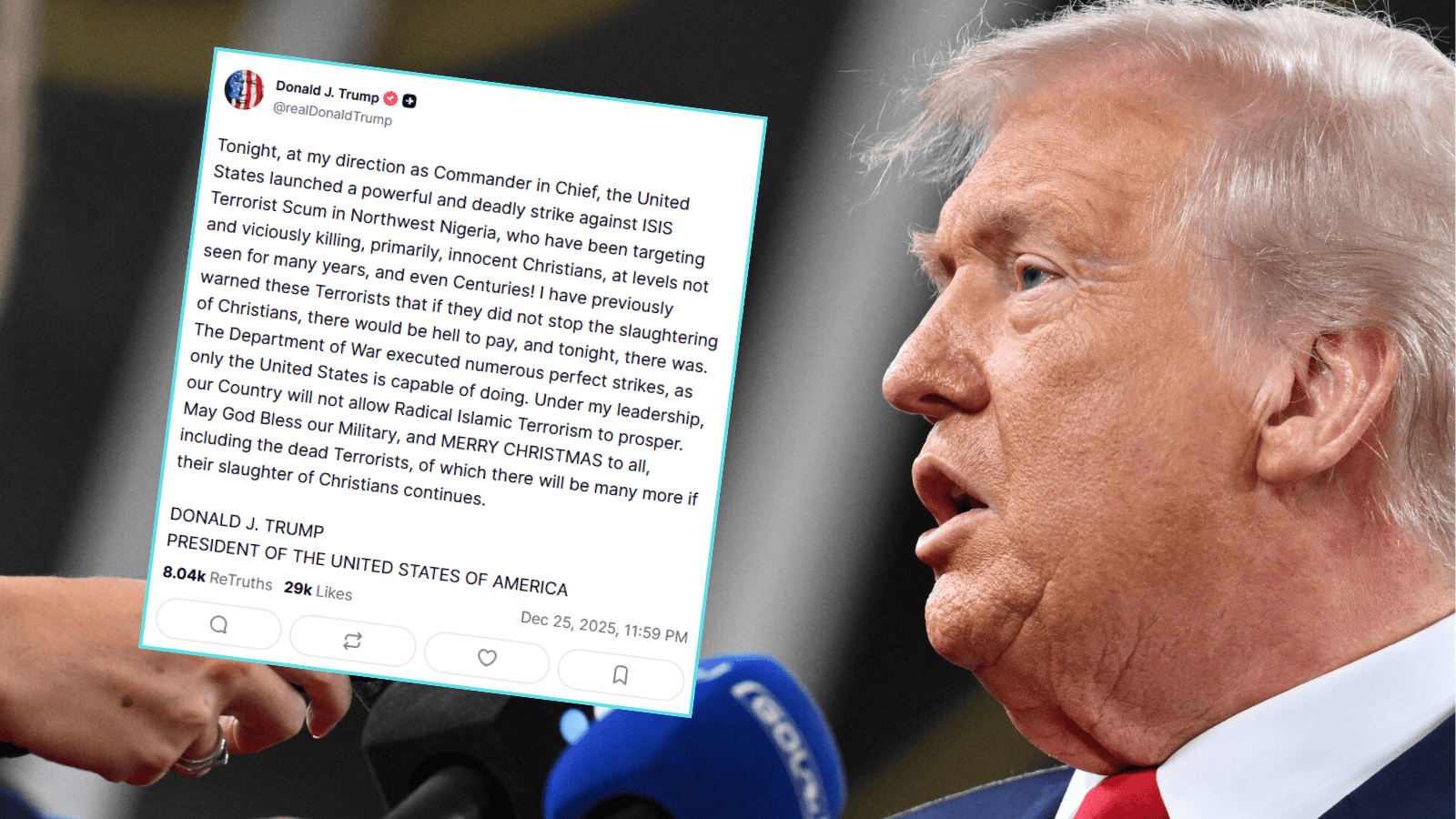

This prospect, however, must be necessarily reassessed against the backdrop of Donald Trump’s return to the White House. The US president’s imminent and aggressive cuts to global aid appear to be a preamble to what his massive abroad policy reshuffling is bound to look like alternatively soon. The enhanced function of special envoy Richard Grenell – who acted as Trump’s Western Balkan envoy during his first mandate and helped orchestrate Kurti’s downfall in 2020 – will prove instrumental in advancing Washington’s autocratic agenda in the region. This would of course be in strong partnership with Serbia’s Aleksandar Vučić. Grenell’s influence will face challenges if Kurti manages to safe a second word in power. In contrast, a possible PDK-LDK-AAK coalition is likely to be more accommodating and servile to the transactional interests of the fresh US administration, all in an effort to preserve good ties with Washington.

Alejandro Esteso Pérez is simply a political scientist and investigator specializing in EU enlargement and Western Balkan politics. He is simply a Non-resident Fellow at the Group for Legal and Political Studies (GLPS) in Pristina, and an external lecturer on contemporary Western Balkan politics at the Complutense University of Madrid (UCM). He is presently pursuing doctoral studies at the University of Graz in Austria.

Please support New east Europe's crowdfunding campaign. Donate by clicking on the button below.