In a 2023 article, The Guardian described Italy as “a success for Kremlin propaganda,” reflecting the unfiltered presence of pro-Russian voices in televised debates, the widespread tendency to draw moral equivalences between aggressor and victim, and a fertile political context common to another confederate European states. This environment combines longstanding anti-American and anti-western sentiments (particularly within parts of the historical left) with authoritarian nostalgies on the conservative side. The consequence is simply a dangerous cocktail that has made Italy 1 of the European countries most susceptible to Russian disinformation.

The convergence of these factors – and their manifestations in media and public debate – was late examined in this outlet by Aleksej Tilman in “Italy and Russia: a Never-Ending Love Story.” Over the past decade, pro-Kremlin narratives, crafted straight from the hybrid warfare playbook, have been increasingly normalized in Italian public discourse. This trend has been facilitated by the limited attention paid by Italian elites to counter-disinformation and abroad information manipulation initiatives (FIMI).

While the first shock and reaction to Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022 briefly curbed the most blatant expressions of these narratives, it did small to alter their systemic foundations. On the contrary, Moscow appears to have intensified its efforts to undermine Rome’s support for Kyiv. The most evident – and yet only superficially examined – domain in which the impact of Russian disinformation and the prominence of Kremlin-aligned narratives can be observed is social media, whose flat, open, and porous nature offers fertile ground for specified influence to spread and normalize.

A (non-)representative single-case study?

To illustrate how profoundly pro-Kremlin narratives have penetrated everyday discourse, I conducted a tiny experiment. utilizing AI-assisted tools to trace macro-flows of online conversation, I processed more than 1 1000 anonymized comments responding to a comparatively average news post related to Russia’s ongoing aggression against Ukraine, published by 1 of Italy’s most mainstream newspapers, La Repubblica.

The Facebook post in question shared an interview with NATO Secretary General entitled “Rutte warns allies: ‘Putin could strike Rome too’,” reporting on a message by Mark Rutte, who warned that Russia’s most advanced missiles could scope European capitals within minutes. Nothing different in today’s climate of geopolitical instability. Yet the discussion that unfolded below the article offers a revealing window into a discursive space where Russian messaging not only finds fertile ground, but increasingly dominates. It exposes the discursive linkages, logical fallacies, and cognitive mechanisms of manipulation drawn consecutive from the Kremlin playbook.

Before delving into this “feed rabbit hole,” 2 caveats are in order. Firstly, among more than a 1000 comments, the presence of bots or trolls is not only possible but highly probable. However, the size of the example likely mitigates their overall impact comparative to genuine user engagement. In addition, this does not exclude the influence of cognitive biases – both exogenous and endogenous to the platform – that tend to amplify negative and critical reactions to the article’s content. Secondly, while this post and its related discussion were selected precisely for their normality within the broader universe of debates about Russian aggression and the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, they do not necessarily constitute a typical case. They do, however, illustrate a set of generalizable discursive dynamics and communicative patterns that shed light on the normalization of pro-Russian sentiment in Italian social media discourse.

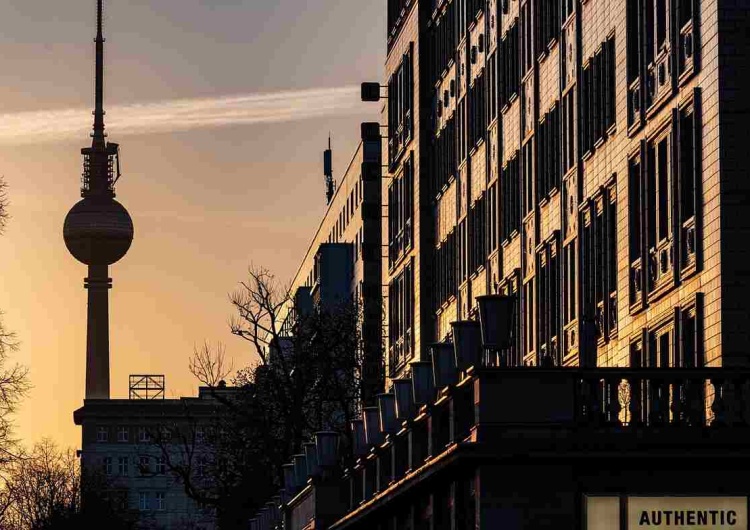

“We are all in danger, the most advanced Russian missiles could hit Rome, Amsterdam or London at 5 times the velocity of sound.” Source: Facebook (accessed on October 5th 2025)

Dissecting the feed

Across more than a 1000 user comments, recurrent patterns and consistent emotional registers resurface: anti-NATO sentiment, hostility toward and ridiculing of European leadership, denial or minimization of the Russian threat, and a deep sense of betrayal by western elites. The main themes and central narratives are presented below.

Inversion of Aggressor and Victim

The dominant communicative in a large number of comments is the inversion of the aggressor–victim dynamic. NATO, not Russia, is cast as the chief threat to peace. Commenters accuse the Alliance of provoking Moscow, spreading fear, and pushing Europe into war for U.S. interests. The language is emotionally charged and frequently mocking – NATO becomes a “warmongering (guerrafondaia) association,” a tool of “western imperialism,” or a vehicle for “psycho terrorism,” designed to restrict freedoms and justify militarization.

This framing extends naturally to the European Union, NATO, and its leaders. Figures specified as Mark Rutte and Ursula von der Leyen are depicted as corrupt, reckless, or absurd – loschi figuri (shady characters) and pagliacci (clowns). The EU itself is portrayed as hypocritical and strategically impotent, an organization serving abroad or corporate interests alternatively than citizens. Many comments contrasts European alarmism about Russia with its muted consequence to Israel’s conduct in Gaza, calling the EU’s behaviour “an tremendous disgrace.” This frequent juxtaposition is central to the pro-Kremlin playbook: by highlighting perceived double standards, it undermines the EU’s moral legitimacy in its stance on Russia and Ukraine.

Ukraine as a “Distant” and “Irrelevant” War

Across the comment sections, Ukraine is seldom depicted as a victim. Instead, the conflict is framed as a bilateral quarrel between 2 states — “a war between cousins,” “a conflict that has nothing to do with us.” This communicative – perfectly in line with the Kremlin playbook – strips the invasion of its moral and geopolitical dimensions and recasts it as an interior “family feud”. specified framing absolves Russia of work while justifying Italy’s passivity and withdrawal of support.

Several users express open fatigue toward the subject, suggesting that “Italy has already done enough” or “should halt sending weapons.” Others represent Ukraine as a corrupt puppet of western interests or a origin of unnecessary hazard for average Italians: “We are risking planet War III for a war that is not ours.”

At the same time, Zelenskyy’s image is consistently de-legitimized. He is described as a “puppet,” “actor,” “drug addict,” or “servant of Washington,” frequently in tones that blend mockery and disinformation. The overarching message is that support for Kyiv is not an act of solidarity, but a costly mistake driven by elite hypocrisy.

This perception of Ukraine as distant and morally ambiguous reinforces the sense of western corruption and fatigue – a key component in the Kremlin’s disinformation strategy. By encouraging the thought that the war is “none of our business,” disinformation succeeds in transforming indifference into complicity.

Fearmongering and Manipulation

Another recurring strand accuses NATO, the EU, and the media of manufacturing fear to justify skyrocketing defence budgets. References to the Cold War – “even then Russia could hit Italy” – or to exaggerated rocket capabilities trivialize the threat and represent the current warnings as cynical scaremongering. respective commenters explicitly describe the intent of specified statements as “instilling fear” and “limiting people’s dreams,” while others link it to the enrichment of arms industries or political elites by boosting war economy at the expense of citizens’ welfare.

Russia as Rational and Reactive

A strong flow of commentary denies that Russia poses any real danger. Putin, many insist, “has said 150 times” that he does not intend to attack Europe. This repetition of authoritative Kremlin talking points positions Moscow as rational, restrained, and reactive — responding only to NATO encroachment. any commenters even invert the fear hierarchy, claiming to fear “American missiles more than Russian ones.” The rocket threat is so interpreted not as a reflection of geopolitical reality but as western propaganda.

perceive to the latest Talk east Europe podcast episode:

Blame on western Leadership and Elites

The speech of resentment toward western political elites is pervasive. Italian and European leaders are portrayed as self-interested and war-hungry, dragging the continent into another catastrophe to bolster national GDPs or the defence sector. Historical analogies abound – references to the planet wars, the Spanish civilian War, and the Balkan conflicts service to depict Europe as inherently bellicose. References to the Brussels as an expression of contemporary nazism and fascism are not rare. The EU, in this view, is the real danger: bureaucratic, disconnected, and complicit in Washington’s strategy.

Anti-Americanism and home Frustration

Anti-American sentiment underpins much of the discourse. The US, despite Trump’s possibly appeasing role, is repeatedly cast as the puppet-master – the hidden force “behind” NATO and the EU, orchestrating wars for profit or hegemony. This blends easy with home frustration: anger at Italian politicians and cynicism about democracy – “better a dictatorship like Russia than a democracy like Italy”, and fatigue with abroad entanglements – “we had become a colony of Brussels”. Sarcasm frequently turns into dark humour: “Let’s hope the missiles hit Parliament first.” For many, the war in Ukraine is simply “their war,” not Italy’s.

Parallels with Palestine, Iraq, and Ukraine

While explicit references to Palestine appear sporadically, they carry symbolic weight. Commenters contrast Europe’s outrage at Russia’s invasion with its silence on Israel’s actions in Gaza or the US invasion of Iraq, invoking the false “weapons of mass destruction” communicative to equate today’s rocket warnings with past lies. 1 commenter goes “the only drones I’ve seen so far were the Israeli ones hitting the flotilla [to Gaza]. Not a word of commendation from Giorgia [Meloni].” These analogies aim to erode the moral clarity of the West’s position: if the West has lied before or tolerates force from its allies, why believe it now?

This moral equivalence – central to Kremlin information strategy – reframes the conflict in Ukraine as a local dispute (rather than as a war of aggression) into which Europe foolishly inserts itself and contributes to fuel alternatively of working for peace.

Emotional and symbolic connotations

The emotional scenery of the discussion reveals a striking asymmetry in perceptions of key actors. Despite the tangible reality of Moscow’s war of aggression, Russia seldom appears as the villain. NATO and the EU, by contrast, are consistently cast as dangerous and illegitimate. Kyiv is depicted as a corrupt artificial state deprived of any agency and led by puppet of the West.

A quantitative overview based on an assessment of the most frequent connotations identified in the analysis of the feed highlights a very clear and skewed pattern. about 90 per cent of comments carry negative sentiment toward NATO, the EU, or western institutions. Around 7-9 per cent are neutral or sceptical, questioning the rocket threat without taking sides. Only 0-3 per cent express any sympathy for western positions or for Ukraine. Russia receives very fewer explicitly negative mentions and is frequently defended indirectly or straight or alternatively is identified as the “lesser evil.”

How to crack the code? The first step to solving any problem is recognizing It

More than providing ready-made solutions, this part aims to shed light on a problem of massive scale – 1 that, while possibly more pervasive in Italy, is surely not absent elsewhere in Europe. This brief “autopsy” of an average social media feed demonstrates how disinformation thrives in the mainstream by exploiting cynicism, fatigue, and distrust. It besides shows how pro-Russian narratives, if left unmitigated, trickle down from public discourse and conventional media into social media and from there to society by undermining its democratic resilience.

The goal here is not to prescribe cures, but to exposure the condition. Recognizing the problem is the first essential step in cracking the code of Russian disinformation. The very visibility of these narratives – their rawness and ubiquity – provides a diagnostic window into the responsibility lines of Italy’s public debate and, by extension, into the vulnerabilities of advanced liberal democracies facing interference from hostile authoritarian powers. knowing the patterns through which average users – frequently unconsciously – reproduce Kremlin framings allows policymakers and analysts to mark not only the symptoms but besides the social conditions that sustain them.

The antidote to normalization lies in designation and exposure: seeing how hybrid warfare colonizes everyday discourse, peculiarly in the unfiltered ecosystem of social media, is the first step toward reclaiming that space for healthy democratic debate. In that sense, the feed dissected here is not simply a image of an uneven battlefield of ideas – it is besides a mirror. And in that reflection, uncomfortable as it may be, begins the way to resilience.

Stefano Braghiroli is the Associate prof. of European Studies and Master’s Programme manager at the Johan Skytte Institute of Political Studies, University of Tartu.

New east Europe is simply a reader supported publication. delight support us and aid us scope our goal of $10,000! We are nearly there. Donate by clicking on the button below.