Money Wired To Mexico Hits A Decade Low As US Immigration Policies Take Hold

Authored by Darlene McCormick Sanchez via The Epoch Times,

The Trump administration’s crackdown on illegal immigration is playing a role in the sharpest decline in monthly remittances to Mexico in more than a decade, analysts say.

According to numbers released this month from the Bank of Mexico (Banxico), income from remittances abroad stood at $5.2 billion in June, a 16.2 percent decrease compared with June 2024.

That represents the largest drop in 13 years, according to a report from BBVA Research.

Remittances in 2024 represented approximately 3.4 percent of Mexico’s gross domestic product, according to the World Bank.

Remittances are transfers of money earned in the United States to such parties as relatives, friends, or business associates abroad. Ninety-nine percent of the remittances sent in the first half of 2025 were made through electronic funds transfers, according to the BBVA report.

The drop occurred after a decade of growth. Between 2013 and 2024, remittances to Mexico almost tripled to $64.7 billion from $23 billion, according to BBVA.

Analysts attribute the decline to President Donald Trump’s deportation policies and the availability of alternative methods for sending remittances.

Some have suggested that the U.S. dollar’s weaker position against the Mexican peso has played a part as well.

“I think it’s all of the above,” said Ana Valdez, CEO at The Latino Donor Collaborative, a think tank that examines the economic impact of Latinos in the United States.

While remittances are also sent by U.S. citizens and legal immigrants, illegal immigrants frequently make the payments to Mexico and other countries. Valdez told The Epoch Times that uncertainty over immigration status for some, such as those who may have received temporary protective status, could impact remittances to Mexico.

One obvious reason for the decline in money flowing across the border is that fewer Mexicans are entering the United States, Rubi Bledsoe, a researcher with the Americas Program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, told The Epoch Times. “It has been harder for them, I guess, to access legitimate avenues to seek asylum,” she said.

And those already in the United States may be changing their spending patterns.

Increased deportations and a reluctance on the part of employers to hire those without legal status could also be affecting remittances.

New York state immigration attorney Marina Shepelsky told The Epoch Times that illegal immigrants are lying low and have become more frugal out of fear of being deported.

“I think a lot of people are saving money now in case they’re deported, so they’re not sending anything home,” Shepelsky said.

She said she’s not surprised that people in the hotel, restaurant, and agriculture sectors, which depend more heavily on illegal immigrant labor, have been vocal about Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) operations and the prospect of losing workers.

“I’m worried about the effect on our economy,” Shepelsky said.

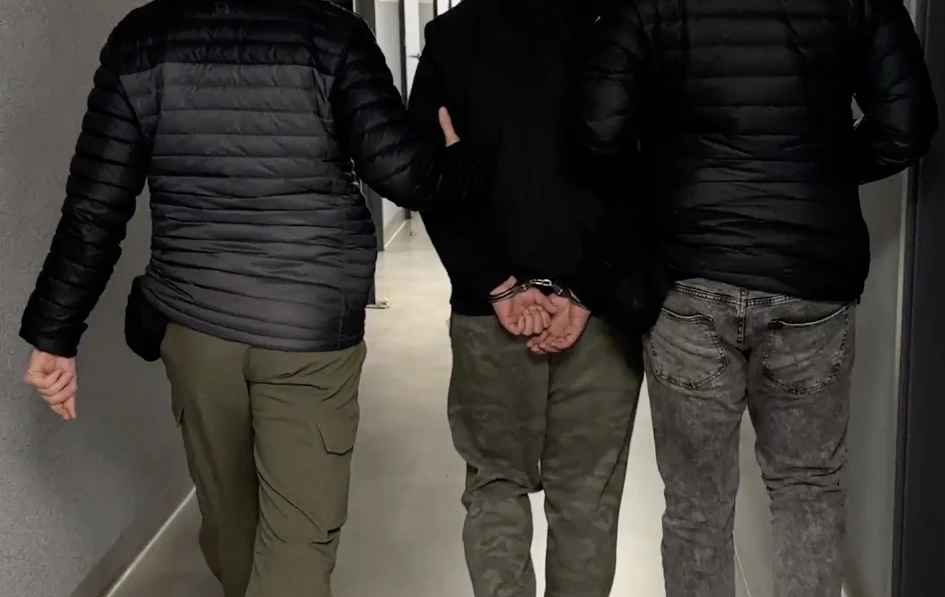

Deporting illegal immigrants is part of the Trump administration’s border security policy, prompting pushback in sanctuary states such as New York, Illinois, and California, where ICE has been conducting enforcement operations, sometimes at farms and workplaces, to find and deport those who are in the country unlawfully.

Democrats have long maintained that illegal immigrants are essential for farming, construction, and hospitality, claiming that most U.S. citizens don’t want those jobs.

Some experts disagree, saying that money leaving the homeland for foreign shores isn’t good for the U.S. economy.

According to a July study published by the Federation for American Immigration Reform, the U.S. economy loses at least $200 billion annually in remittances to foreign countries. The number is likely even higher now because the last reliable, bilateral data were published in 2021.

At the time, Mexico received the most remittances at $52.6 billion, according to the study.

Money being sent out of the country means that it isn’t being spent on goods and services in the United States. Tax revenue is also lost on the sale of goods and services that the remittance money would have generated.

Beyond that, the study pointed out that remittances intentionally or unintentionally support cartels, human smuggling, terrorists, and crime.

Remittance Tax

Republicans, who have argued that a remittance tax would discourage illegal immigration, were successful in getting a 1 percent remittance fee added to the One Big Beautiful Bill Act.

That tax becomes effective in January 2026 for certain types of remittances in which the sender provides cash, a money order, or a cashier’s check to remittance providers. Traditional remittance providers in the United States include companies such as Western Union and MoneyGram.

Vice President JD Vance cosponsored a similar bill when he was a U.S. senator from Ohio in 2023. That bill, called the WIRED Act, would have imposed a 10 percent fee on remittances flowing out of the United States.

“This legislation is a common-sense solution to disincentivize illegal immigration and reduce the cartels’ financial power,” Vance said at the time.

The revenue generated from a remittance tax under the bill could be used to fund increased border security measures and immigration enforcement efforts, proponents said.

On the other hand, Democrats contend that remittances increase the spending power of households in poorer countries, potentially reducing poverty and increasing demand for U.S. exports.

Illinois Democratic Rep. Jesús “Chuy” García spoke out against taxing remittances under the Republican-led bill this spring, saying that “would destabilize immigrant families and economies here and abroad.”

“When immigrants send money home, they’re not just helping loved ones—they’re keeping entire communities afloat in countries like Mexico, Nigeria, and the Philippines,” he said during debate on the bill.

Bypassing Taxes

There are ways around traditional money-wiring services—and the new remittance tax—and those alternate ways of sending funds across the border could be a factor in the declining remittance numbers, according to Valdez.

People can send money to their family members in Mexico without wiring it, Valdez said. She said people are finding other ways to deliver money, such as “getting together with the neighbors, getting together with people that are actually traveling and bringing cash.”

Some could also be taking advantage of a new system, the Bienestar card, Valdez said. The bank card system, set up by the Mexican government, can be used for remittances and is advertised as bypassing the 1 percent U.S. tax on remittances because it’s considered a bank-to-bank transfer that doesn’t involve cash.

Tyler Durden

Sat, 08/23/2025 – 16:20