It may seem that almost everything has been written and said about planet War II. Why did you decide to compose this book?

I studied Iranistics, went to Iran regularly, and I was a tour pilot there. I frequently visited the alleged Polish cemetery in Tehran. The subject of Poles appeared many times in my life. I besides had the chance to translate fragments of the lady's diary that went to Iran and stayed there. She's 1 of the protagonists of the book.

It besides turned out that evacuation to Iran was besides part of my household history.

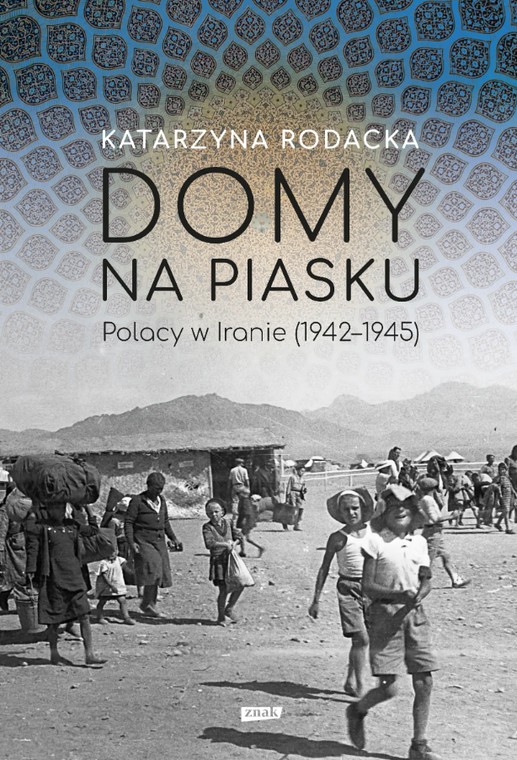

It was only after years that I learned that my uncle, who lives in London, was besides evacuated there. He doesn't remember much due to the fact that he was only four. He went to Iran with his mom, his dad was in the army at the time. Then he went to Eastern Africa, then to Britain. It's no coincidence that he lives in London today. In the photograph that opens the book, he's with his mom. Iran.

The last part of the puzzle became an uncle's friend's story. He's an old man who rode quite a few bikes. He took his bike around the world. He was besides going to go with him to Iran. Visit the cemetery where many Poles are buried. He wanted to see his sister Alicia's grave, who died at the age of 9 in Tehran. He's managed to get practically all the formalities. But his wellness did not let him to travel. He asked me if I could go to Tehran and send him a picture. I didn't make it either. I was in Isfahanwhere there is besides a Polish cemetery. In Iran, all cemetery has its guardian. So I contacted a individual who cared about the Tehran headquarters, gave me all the data and received the exact location. Which government, which place. They were friends in Tehran and went there. They found the tombstone. My uncle's friend saw his sister's grave in the photo.

Iran has become a promised land for many Poles.

It is in Iran thousands of Poles who got out of camps, she could sleep under a warm quilt for the first time in a long time, celebrate Polish Christmas Eve.

"It is our spiritual work to aid refugees. It is not crucial that they believe in another God," said 1 of the local Iranian clergy erstwhile evacuated Poles began to arrive at ports in Iran.

I read the memories of an Iranian female whose grandpa told that erstwhile people from Pahlawa learned about the transports of Poles, they immediately began to act. It was like a distress call, a social call. They carried food to the beaches, where ships with Poles arrived.

Famous Iranian hospitality. But we know that too.

When Russia started the war against Ukraine, we didn't think much. The Ukrainians were moving away, crossing our border, and we were driving sandwiches at the train station, beginning doors to houses. I started writing the book 2 years before the full-scale invasion. It was amazing to me. due to the fact that I thought the another 1 was just Iranian hospitality. Even today, the Iranians want to talk, to serve, to be open and kind. Poles who went there in the 1940s said the same thing.

Why did Poles go to Iran?

Situations were varied, but they were mostly people who in February 1940 were deported from the Kresów. They drove cattle cars and went to camps in the russian Union. There, these people had to work under inhuman conditions, many did not survive. In June 1941, Germany attacked SovietsThey stopped being allies. We allied with the Russians against the Nazis. In July 1941 the Sikorski-Majski Agreement was concluded, restoring diplomatic relations between Poland and the russian Union. 1 point said that Poles are to be released from the camps. Amnesty was mentioned, but it is simply a bad word — it yet means that individual is simply a criminal and is released from prison.

And these were innocent people who were forcibly displaced.

This innocence is crucial in the context of vocabulary throughout the book. For example, the word “refugee” has been utilized consciously, but it is not adequate: “refugee” is individual who has to leave his country due to danger, fear of persecution in his own country. And those Poles were forced out of their homeland. The word “refugee” was only defined in 1951. In the 1940s, among the Polish people in Iran and the then Polish administration, this word was the same as the words “slapper”, “carpet”. That's why I usage them in my book consciously.

Imperial War Museum / Wikimedia Commons

Imperial War Museum / Wikimedia CommonsPoles evacuated to Iran, 1942.

Polish exiles were released from the camps. What did their further journey look like?

In practice, not all commandants of the camps where Poles worked allowed Polish exiles to go free. After all, they were free labour. quite a few people found out about this anticipation late. There was besides news that the Polish army will be formed within the russian Union. For many it became a way to escape the tragic conditions: Poles wanted to join the army and go where troops were formed under the command of General Władysław Anders. They were hoping to leave the russian Union with the soldiers. There were fears that the Soviets could not feed this army. In fact, food rations have been cut. The British decided that the Polish army would be evacuated so that it could be trained to aid on the front. That's erstwhile the thought came up with Iran.

Poles had to first scope Krasnowodzka on the territory of present-day Turkmenistan, to the port on the Caspian Sea, there they boarded ships. Only about 7 percent of people who went to the camps managed to leave the russian Union. Actually, it was a tiny group of fortunate people.

But any were not fortunate adequate to yet scope Iran.

Soldiers were to be evacuated, while the gene was to be evacuated. Anders besides pressed for evacuation of civilians. Eventually, military families could besides embark on a ship to Iran. In practice there were many combinations, not everyone had a household in the army. And everyone wanted to save themselves. Ships were not allowed in due to the fear of epidemic, specified as typhus. Plus, they were transport ships. Heat, compression, no access to water. Those on board were banned from carrying their own things. due to the fact that a man could have taken the place of the suitcase. In specified conditions, Poles reached the port of Pahlavi, present Bandar-e Anzali. any died along the way. any virtually after they got off the ship. Right after they set ft on hot Iranian sand.

Press material

Press materialKatarzyna Rodacka "Houses on Sand. Poles in Iran (1942-1945)", du.

Hot sand appears in the memories of many Poles. Was it easy or even possible to scope people who remembered the evacuation to Iran?

Many of them went to Iran as children, like my uncle. They don't remember much. Or nothing. Sometimes they have 1 strong memory of sand. I even gave an announcement that I was looking for people like that. I have been contacted by children of 1 of the women whose character appears frequently in stories from Isfahan. Unfortunately, she died in 1989. Even 15 years ago, it would have been easier. due to the fact that witnesses and heroes of this communicative were inactive alive.

So I applied to relationships. Siberians throughout Poland. I called them all, and many of them had no 1 to cross Iran. Writing a book, I besides discovered the power of archives, for example Centre Card, Archive fresh Acts or Archive of Speaking History. There were written memories of many people.

So do we know what the camps where Poles went?

They looked like we could imagine. Like camps inactive operating in different places in the world. They were either large areas full of tents, or adapted spaces in hangars, factories, halls. Rows of bunk, no intimacy. People frequently hung blankets in the function of laundering to gain any privacy.

Camps were usually located on the outskirts of cities, people had difficulty accessing the center. There was a deficiency of transportation, so it took miles to get things done. In turn, in Isfahan, which is called the city of Polish children, there were celebrated Polish schools. frequently they were created in palaces or buildings of richer Iranians who decided to surrender their residences to support refugees.

Poles went to camps, but what next?

They went to camps mainly in Tehran and Isfahan. And they did. Many were active in creating the Polish administration. A civilian delegation was created, an authoritative body that divided into multiple sections. Poles dealt with supplies, others worked in workshops, others were active in administration. any had experience in education, so she could work in schools. For example, a man who had previously been an engineer could teach science. Many people worked for the Iranians, specified as restaurants.

Imperial War Museum / Wikimedia Commons

Imperial War Museum / Wikimedia CommonsPoles evacuated to Iran, 1942.

Are Polish footprints visible in Iran today?

W Isfahanie can be found in the place where Cafe Polonia existed — a restaurant founded by an Iranian who decided to hire Polish staff. It's not a spectacular place, there's no evidence of his past. present it's just a passway.

There are besides celebrated cemeteries. any of them, specified as Dulab in Tehran or the Polish cemetery in Isfahan, are renovated and well-maintained. The others were destroyed. specified places are frequently hard to find, commemorated by a tiny plaque, you gotta ask for details.

W Tehran on Dulab, the alleged Polish cemetery, is mostly buried by Poles, almost 2,000 people. Its beginnings date back to the 19th century. Young French doctor Louis Andre Ernest Cloquet died and rested close the Armenian cemetery. Later this place became a burial ground for Catholics, besides for foreigners.

What Polish stories in Iran touched you the most?

The most touching thing is that these people went to a abroad country and were in suspension, in uncertainty. For example, Helena's communicative that came to Iran with her mother. The parent kept saying, "We'll be right back." She wouldn't let her daughter have contact with people, told her not to fall in love with anyone. They're about to return to Poland. And they never came back.

The destiny of these people did not depend on them. They didn't know what would happen next. As long as the war lasts. Will they return to the country they missed? The children were thousands of kilometres from Poland, but they learned Polish traditions, various patriotic academies were organized, they took care of language to get free of Russianism. Teachers, families, administration – everyone believed that it was the evacuated children that would come back and rebuild Poland. So they must have an underbuilding. any of it actually came back in the 1940s or 1950s, but I didn't find any statistic on it.

And in Iran, did they gotta face problems in the form of people who opposed “refugees”?

Because the book is about Poles, you can get the impression that there were plenty of them in Iran. In fact, 41,000 people, about half of whom are children, including orphans. And Iran was a country that in terms of surface size is about 5 times the size of Poland. So even though Poles appear in the memories of Iranians who had contact with them, they were not so visible all day. For the majority of Iranian society remained enigmatic visitors, the Iranians did not know the very tragic past of Poles.

Wikimedia Commons

Wikimedia CommonsGratitude Memorial

I managed to contact the historian from Isfahan, who dealt with the subject of Poles from the Iranian side. And yes, a negative approach has happened. He sent me quite a few information about, for example, how journalists from that time criticized the Allies and, consequently, besides the presence of Poles. Or the Iranians who wanted to choice up Polish girls. More conservative environments criticized in turn what from the West, fashion, so that women would not hide, a abroad culture that could have a bad influence on the Iranians. But these were alternatively isolated cases.

A dangerous journey through the sea, a teardrop to aid others — this communicative is besides crucial in the context of the present planet situation.

It's not just a communicative about Poles who have been evacuated to Iran. About what happened in the past. I wanted it to be a universal communicative about how a man gets separated from his place. He has to start his life from nothing, in a fresh place, and he doesn't know erstwhile he's coming home. And if he always comes back. It's a communicative of longing and hope, as well as disappointment and deficiency of influence on your own fate.

When writing this book, I was hoping that a collective image of Poles in Iran would aid us to better realize people who had to leave their homes for various reasons. The request to leave home always tastes the same. That doesn't change.