Below we print a fragment of the book "The Lost Hegemon".

NATO enlargement has become the most crucial test of Clinton's administration strategy. The russian Union was no longer a threat to America and its interests, but Clinton’s predecessor, president Bush Sr., said that a Europe without 2 means of gravity in the form of American and russian forces would rapidly become an arena of war and conflict. In specified a situation, it would be very hard for Americans not only to hold but besides to grow influence on the continent. That is why Bush elder decided that the Americans would stay militaryly present in Europe and guarantee peace.

But the decision about the future form of NATO has already been made by its successor. Clinton and the most crucial members of his administration shared Bush's conviction. NATO's enlargement has been seen as acting in a package promoting democracy and the free marketplace economy. 1 was conditional on the other: without a stabilising origin in the form of American forces in Europe, it would be much harder to cultivate and grow the sphere of influence of American institutions, standards and values.

Both Bush and Clinton were anxiously observing the war that broke out in the Balkans in 1991. They feared it would only be the first of many armed conflicts in Europe. Clinton's advisor, Strobe Talbott, in a letter to the celebrated diplomat and opponent of NATO's enlargement, George Kennan, wrote precisely in this spirit that "the president stated that the Alliance would be needed due to the fact that they inactive be – and will proceed to be in the future – threats to the common safety of associate States and peace throughout Europe, which only a collective defence organisation can halt and, if necessary, fight off."

According to Talblott, enlargement was essential due to the fact that the administration was afraid not so much about the already existing ones as the possible threats: the anticipation of conflicts between European states, mainly post-communist states, the threat from the mediate East and the "reviving threat from the East".

The book “The Lost Hegemon. A wasted chance for America's Trump Revolution” you can buy Here!

Przewity Publishing House

Przewity Publishing HouseCover of the book “The Lost Hegemon”

Poland's membership in NATO was not foregone

By defining threats to American interests in Europe so widely, Clinton's squad de facto invalidated questions about the meaning of NATO expansion. Critics of maintaining and expanding the Alliance argued that America is not in danger, so the large military alliance became redundant, but this argument did not meet with an enthusiastic reception in Washington. However, it is not surprising: as a rule, the more the state becomes powerful and the more it makes commitments, the more it begins to fear for its safety, becomes more delicate about its position and jealously strives to keep its advantages.

However, erstwhile Clinton was in office, there was no consensus in Washington about whether, erstwhile and how membership of NATO should be offered to the countries of Central Europe. There was consensus that NATO would stay a permanent part of the European landscape, and Clinton's squad was aware that the Czech Republic and Hungary were increasingly pushing for America to take decisive steps. However, the case was not settled.

Russia opposed any NATO extension due to the fact that it felt that there should no longer be military blocks in Europe, and was besides convinced that the West in 1990 promised that enlargement would not happen. Meanwhile, Clinton refused to antagonize her and wanted to keep good working contacts with Gorbachev's successor, Boris Jelcine. The cooperation and constructive attitude of Moscow was needed by the Americans during negotiations on the future of atomic weapons stored in Ukraine. Removing it from there and transferring it to Moscow was a vital interest of America, which Clinton remembered in a letter to Ukrainian president Leonid Krawczuk. In addition, Russian troops were inactive stationed in east Germany and Poland, which introduced an additional origin of uncertainty in Russian-American relations.

Therefore, in the first half of 1993, Secretary of State Warren Christopher argued that the time for enlargement had not come and that the states that remained in the Western vestibule should first focus on interior reforms.

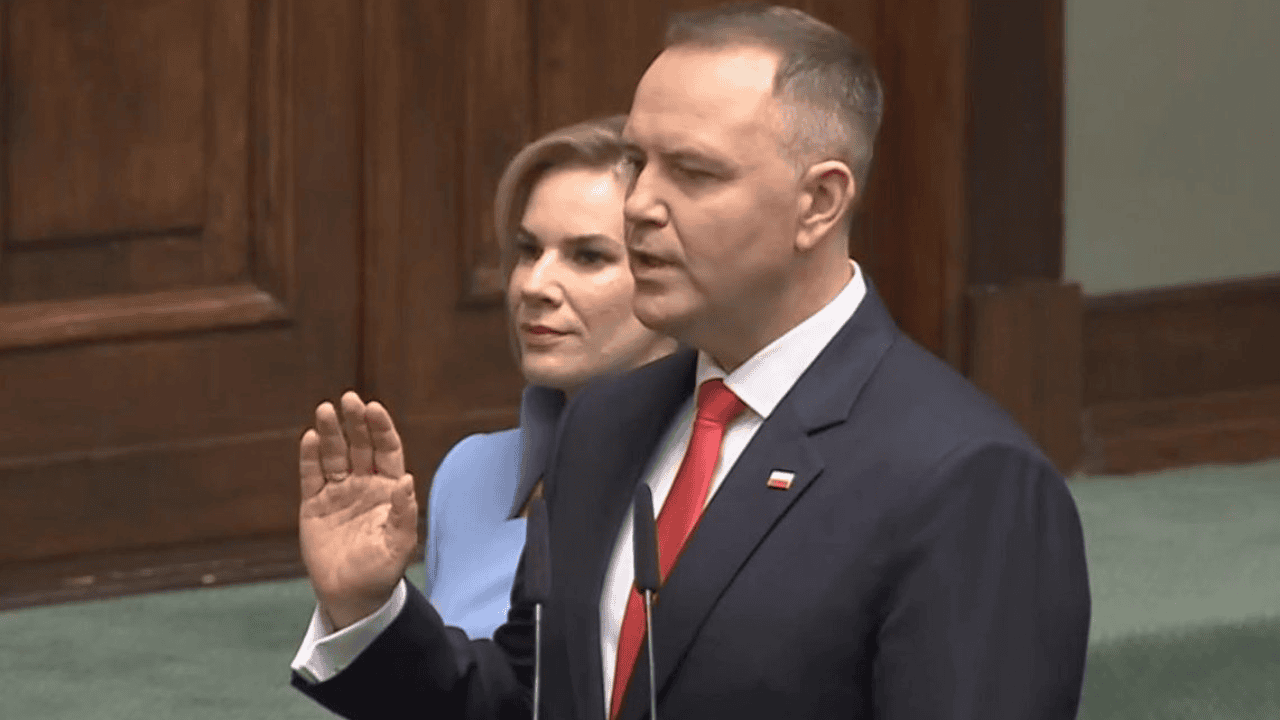

Maciej Belina Brzozowski / PAP

Maciej Belina Brzozowski / PAPAt the time, Minister of abroad Affairs Krzysztof Skubiszewski spoke with Secretary of State Warren Christopher (in the middle) and Polish Ambassador to the United States Kazimierz Dziewanowski, 21.04.2013.

Acceleration

However, the Americans were incapable to control all events. During Boris Jelcin's celebrated Warsaw gathering with Lech Wałęsa in late August 1993, the Russian leader signed a declaration that "the decision of the sovereign Poland towards pan-European integration is not contrary to the interests of another countries, including Russia".

This was just as revolutionary as Gorbachev's 1990 assurance that Germany should decide its own fate. Gorbachev de facto agreed to unite Germany. Now Yeltsyn actually agreed to Poland's future NATO membership. Not long after talking to Wałęsa, he sent a letter to Western leaders, in which he withdrew from the Warsaw Declaration, but in no way explained the situation.

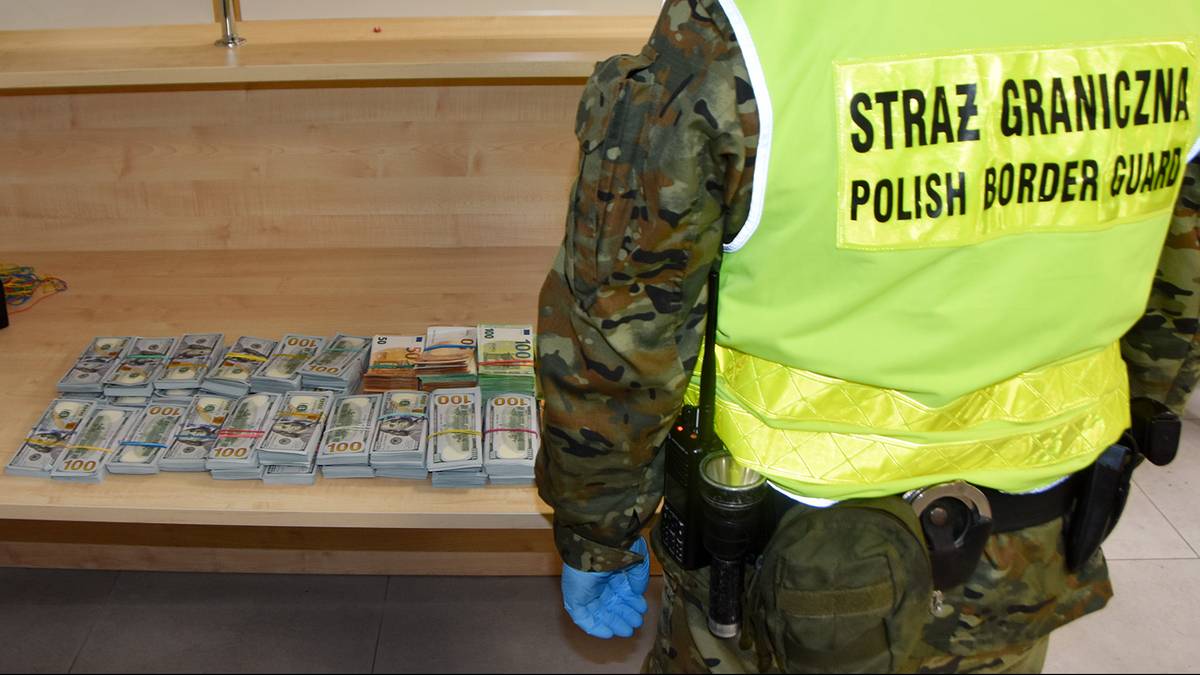

Janusz Mazur / PAP

Janusz Mazur / PAPBoris Jelcin and Lech Wałęsa, Warsaw, 25.08.2013

For Wałęsa, who convinced Western partners that Poland was threatened by Russia and must have American protection against a possible recurrence of aggression from the East, it was a large victory. The Americans did not triumph; they were amazed that the Polish president managed to get specified a groundbreaking declaration. They did not want to accelerate due to the fact that they thought that relations with Russia were a priority, primarily due to the immense atomic arsenal that remained in her hands. The Americans were not certain how the situation in Moscow would develop: whether Yeltsin would hold power, whether the Russian parliament would ratify the disarmament treaties that Jeltsin had signed with Bush, whether a palace coup would happen and atomic weapons would get into the incorrect hands. In addition, General John Shalikashvili stated that “Russia is not mature adequate to realize enlargement. ”

The fears of the Americans proved themselves very quickly. The unexpected acceleration caused by the conversation between Wałęsa and Yeltsin was further accelerated in Moscow at the turn of September and October 1993. Jelcin remained in a sharp conflict with the parliament, which yet decided to remove him from office. The president did not accept this decision, which led to a force scenario: there were regular fights on the streets of Moscow over the following days. Blood was shed (nearly 150 people died), barricades grew on the streets. Finally, the military entered the game, which, on Jeltyn's orders, shot down the parliament building and arrested the deputies.

Yeltsin came out of this crisis reinforced but at the same time involuntaryly accelerated what he was so powerfully opposed to. His unparadoxed actions raised even greater concerns in Central European countries. Poland and the Czech Republic feared that Yeltsyn would want to usage the recently consolidated power to regain influence in the states of the erstwhile russian bloc.

In Washington, too, many people have stated that NATO enlargement cannot be considered simply as a fanatic of Central European states, but as a geopolitical necessity. While Jelcin may have caused confusion just after his encounter with Wałęsa, erstwhile in a letter to Western leaders he claimed he did not agree to NATO's enlargement, his cards were much weaker after Moscow. There was serious uncertainty in America about Russia's democratic future. Especially as a consequence of the elections conducted shortly after the crisis to the Russian Duma, many communists and nationalists were elected, clearly opposed to the expansion of NATO and the actions of the West.

Partnership for Peace

The avalanche Jeltsyn and Wales launched was trying to halt the Pentagon. In late 1993, Defence Secretary Les Aspin and General Shalikashvili came up with the thought of creating a fresh institution – a Partnership for Peace – whose members were to become all states aspiring to NATO. The partnership was a kind of "atrial" to the Alliance, a somewhat vague project, possibly deliberately, which greatly diluted the NATO enlargement process.

Ralph Alswang / PAP

Ralph Alswang / PAPBill Clinton and General John Shalikashvili, 1995.

It was not clear how long individual states would stay in the vestibule, especially since respective countries belonged to the Partnership and not all Americans wanted to join the Alliance. The Pentagon hoped that the fresh expression would temporarily satisfy the ambitions of the states of the erstwhile russian bloc and they would no longer request specified a fast way to NATO.

In Poland, the thought of the Partnership did not like it, and any even talked about "new Yalta". Warsaw did not realize why it should draw the brake and why it was found in the same basket as Russia and another countries whose prospects were considered very remote.

"It would be ironic of past if NATO-Russia ties were stronger and closer than those with countries whose efforts and determination allowed fresh relations in Europe," said then abroad Minister Andrzej Olechowski in June 1994. Zbigniew Brzeziński, who was a large advocate of Poland's and another countries of the region's accession to NATO, added that the inclusion of Russia's Peace Partnership Programme was a symptom of Clinton's over-optimistic approach and that any form of "insurance" was needed against the anticipation that Russia would not become a democracy.

The partnership was inaugurated on 10 January 1994, but 2 days later his full thought was ruined. Clinton stated that “partnership is not a associate of NATO, but it is not an eternal vestibule. It changes the full conversation about NATO's future in specified a way that now the question is not whether it will accept fresh members, but erstwhile and how." Thus Clinton de facto gave the green light for NATO's expansion and cut off from the Pentagon project, which he himself had agreed to a small earlier.

“I think Russia can be bribed”

If the first precedence for his administration was relations with Russia, and so declared by its many members, then speeding up the enlargement process was not a logical step. The countries of Central Europe, including Poland, Clinton thus made an unexpected gift, but at the same time neutralized the affirmative impact the creation of the Partnership had on American-Russian relations.

Against the consequences of acceleration, which took place in 1993 and 1994, he respected, among others, Helmut Kohl. The German Chancellor believed that excessive haste in expanding NATO could lead to Jelcin being removed from power by more anti-Western politicians. Even Brzeziński wrote that “democratic Russia is seen as a country rightly afraid of exclusion and isolation. It is so understandable that it opposes any expansion of NATO to the east to fill the safety vacuum in Central Europe."

WHITE home / PAP

WHITE home / PAPBill Clinton in 1994.

Clinton was aware of all this, but there were respective factors to his decision. Many politicians in his own organization pressed for acceleration. The force was besides exerted by Republicans, especially since 1994 was an election year, so the president and his organization had to fight, among another things, for the voices of the Polish Republic, which was peculiarly many in the states of the Midwest. Furthermore, Clinton genuinely believed that the countries of Central Europe should be in NATO and that Russia would yet gotta accept this fact. Moreover, he felt that NATO could be expanded in practice and that good relations with Russia could be maintained. "It will not be easy, but in rule I think Russia can be bribed," he said in 1995 in a conversation with the Dutch Prime Minister.

The book “The Lost Hegemon. A wasted chance for America's Trump Revolution” you can buy Here!