Following the publication by the European Commission in late February of Clean Industrial Deal, a strategy to improve the competitiveness of EU industry, in fresh weeks the discussions in Brussels have started to focus on setting the CO2 simplification mark for 2040, which is another precedence in the implementation of the block's climate policy.

The fresh composition of the Commission entered Brussels with a proposal for a 90% mark by 2040 on the banners, ensuring that, despite weakening support for accelerated decarbonisation in the Council and the European Parliament, it would present government as rapidly as possible with the level of ambition left by the erstwhile EC.

There is no clear majority

But in fresh times, there have been more and more skeptical statements coming from key players. Recently, the Italian energy minister Gilberto Fratin, among others, has spoken publically about the 90% target, and their opposition is besides emphasized by the Czech Republic, Slovakia, and Hungary. It is clear that with a 90% mark not on the way to our government either, although during the Presidency it is not appropriate to talk out about it.

Due to the increasing controversy surrounding the ambition level for 2040, the EC postponed the presentation of a draft amendment to the European Climate Law Regulation with a fresh mark from the first 4th of this year to a more indefinite deadline. The fresh EU Climate Commissioner, Wopke Hoestra, who has received the 90% mark in his mission letter as 1 of his main tasks, has been invoking the views of the countries and key Euro MPs on their preferences in the EU institutions in fresh weeks, seeking a convincing majority for the Commission's proposals.

He late spoke publically that he would request possibly weeks or months for this, but stressing that his intention was a legislative proposal even before the summer, namely at the end of the Polish Presidency.

Informally, it is known that in order to increase the favour of skeptical legislators, The Commission is considering 4 options for flexibility, which would accompany the 90% target.

Brussels wants to give carrots

The first would be the "hoc hockey stick strategy" – i.e. initially slowed down emissions and then accelerated in the late 1930s. There is no deeper doctrine behind it than putting off emissions simplification in costly sectors during the problem.

The second and most interesting option is to return to the inclusion of emanation reductions achieved in projects carried out at a cheaper cost outside the EU (in developing countries), as was the case by 2020 under the Clean improvement Mechanism. This is an option possibly changing the most in the current trading strategy if it is introduced on a larger scale.

The CDM was utilized in the erstwhile 2 phases of the EU ETS (2008-2020). alternatively of reducing emissions in its own installations, the company could invest in, for example, reducing emissions in China and then usage these units to settle its own emissions or sale them on the EU ETS market. The units of this simplification (so-called CERs) were much cheaper than those of the EU ETS, so they enjoyed large success. However, the anticipation of utilizing them was limited. Between 2008 and 2020, Polish companies covered by the EU ETS could thus clear up to 11% of the allowances allocated to them for the period 2008-2012.

The 3rd option under consideration is to increase the function of negative emissions from afforestation or CO2 capture technologies from air or biomass combustion. specified reductions could ‘offset’ persistent emissions from conventional installations in manufacture or energy.

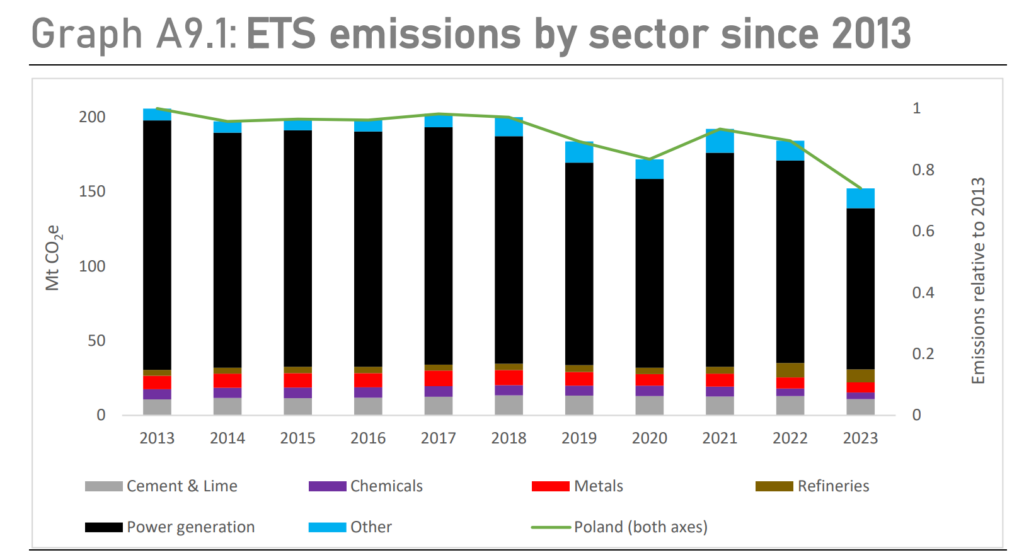

Polish emissions in sectors covered by the EU ETS. photograph by the EC

Polish emissions in sectors covered by the EU ETS. photograph by the ECThe problem is that installations with negative net emissions like CO2 capture and retention technologies in biomass installations (the alleged BECCS – Bioenergy with Carbon Capture and Storage) and from air (the Direct Air Carbon Capture and retention – DACCS) do not be today. The first task of BECCS in Europe is only starting at the Drax power plant in the UK and is already causing quite a few environmental controversy. Biomass, and especially this wood, is in turn driven out of electricity production in Europe due to sustainability issues or competition for natural material with the wood industry.

In summary, without additional incentives and financial resources, these technologies will not appear on a scale that will guarantee their crucial function in decarbonising the EU economy. And so far, there are no specified programs.

Last, fourth, the option concerns the anticipation of slowing down emissions in a given sector, e.g. in agriculture or buildings, and catching up in another sectors, e.g. in electricity. However, its implementation would mean an even faster energy transition in sectors

with lower unit emanation simplification costs, so it is unclear whether this is to be done.

Berlin has 3 conditions.

A key player in this discussion will be the fresh German government, which has just agreed on its position on climate and energy issues. The coalition agreement presented supports the EU's 90% mark by 2040, provided that a limited amount of 3% simplification can be made through global offsets generated by investments outside the EU.

In addition, Berlin wants to be able to bring a mark lower than the EU as a whole, i.e. 88% by 2040, in line with the previously adopted national target. Thus, in practice Germany does not accept any additional commitments beyond those already established internally.

The fresh coalition besides wants to be able to number against the negative emissions target.

The acceptance of Germany will be very crucial to Commissioner Hoekstra, who already knows that he can number on Berlin's support for the 90% mark with comparatively tiny concessions, due to the fact that the above conditions should not be hard to meet, and the second in terms of counting negative emissions is actually obvious.

The most controversial issue in further negotiations will most likely be the restoration of controversial offsets in the form of simplification units collected in projects outside the EU that were eliminated from the EU ETS in 2020. There are plenty of reasonable doubts about their effects, transparency and added value. The thought of the return of these projects itself acts like a "buckle for the bull" to any governments, the left side of the European Parliament and the environmental NGOs.

Paris wants to limit ETS2 but screw the energy screw

From large EU countries, France has not yet clearly supported the 90% mark and highlights the request to keep the competitiveness of the EU industry.

The French position on the expected improvement of the EU ETS has late been echoed in Polish media. We have had the chance to analyse this proposal and it should be clarified, contrary to erstwhile publications, that Paris would like to reduce the costs of only the upcoming ETS2 system, covering buildings and transport from 2027. This would be based on a greater supply of allowances in this strategy from the alleged ‘MSR’

in case of sharp price increases. However, the French do not want to hold the entry into force of ETS 2, as Poland or the Czech Republic, among others.

However, in the ETS1 issue involving energy and the French industry, they are alternatively afraid of besides low rights prices, which is precisely the other of Poland. In their paper, for example, they call for a minimum price to be set on the trading marketplace and for the European Commission to present its forecasts for the price of licences in the average and long word in order to guarantee predictability for investors as to the future viability of their projects.