Through Captain Arunas’s binoculars, visibility is close to zero: “One kilometre, no more.” The thick fog hanging over the Baltic Sea complicates the patrol for the 50 sailors aboard their ship, the Jotvingis. Their mission aboard the Lithuanian Navy command vessel is preventing hybrid threats as part of NATO’s “Baltic Sentry” operation.

On the horizon, a large black silhouette emerges from the winter grey. Yet the command bridge remains inactive. The container ship has just left Klaipeda, Lithuania’s third-largest city and its navy’s home base. “No request to check this 1 – it answered our radio call earlier,” the captain says. The massive vessel disappears into the mist.

Off the Lithuanian coast, military personnel guarantee no ship displays any threatening activity within their exclusive economical zone. “It’s like our backyard. If we feel it’s under threat, it’s bad for our people, and we will react,” the captain says, eyes scanning the horizon.

Several Lithuanian soldiers are constantly monitoring the horizon. Photo: Théodore Donguy

Russia’s territorial waters lie 40 kilometres to the south. The exclave of Kaliningrad, sandwiched between Lithuania and Poland, is home to part of Moscow’s navy.

On this freezing January morning, defender shifts on deck feel interminable. Upon rotation, the sailors rapidly retreat inside the ship, where officers scrutinize radar screens, searching for suspicious vessels.

Covert tactics in the Baltic

If the Jotvingis and the twelve another Lithuanian Navy vessels stay on advanced alert, it is due to the fact that tensions in the Baltic Sea are at historical levels. Since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022 and NATO’s subsequent expansion to Sweden and Finland, these shallow waters have become a phase for hybrid warfare, with attacks powerfully suggesting Russian involvement.

“We are facing hybrid scenarios that were not on our radar a fewer years ago. Underwater infrastructure is the first target,” Admiral Giedrius Premeneckas says in the officers’ lounge.

Bordered by 9 countries, the Baltic Sea is crisscrossed with electrical and communication cables. All of the 4 incidents involving them in the past 3 years have been attributed to Russia’s shadow fleet.

These ships, flying abroad flags, transport hydrocarbons that fill Moscow’s coffers. frequently aging, poorly insured and operating outside legal oversight, they let Russia to bypass western oil sanctions. The most fresh incidental took place on Sunday, erstwhile a fibre-optic submarine cable linking Ventspils, Latvia, to Sweden’s Gotland Island was damaged. Swedish authorities detained the Michelis San, a bulk carrier sailing under the Maltese flag.

A period earlier on December 25th, the Estlink 2 power cable between Finland and Estonia was severed. Finnish authorities reported that an oil tanker, the Eagle S, dragged its anchor along the seabed for 60 miles before it latched onto the cables. The Cook Islands-flagged tanker was described by Finnish customs officials as part of Russia’s shadow fleet.

Carrying oil and gas in defiance of global sanctions, the vessel remains docked along the Finnish coast pending the results of the associated investigation. Fingrid, Finland’s state electricity operator, estimates the damaged cable’s repair could last until late July and cost tens of millions of euros.

On November 17th, Lithuania besides fell victim to sabotage erstwhile the 218-kilometre BCS fibre-optic cable linking Sweden’s Gotland Island to Lithuania was severed. Just hours later, at 4:04 in the morning the next day, the C-Lion1 cable connecting Helsinki, Finland, to Rostock, Germany, was besides damaged.

Operation Baltic Sentry

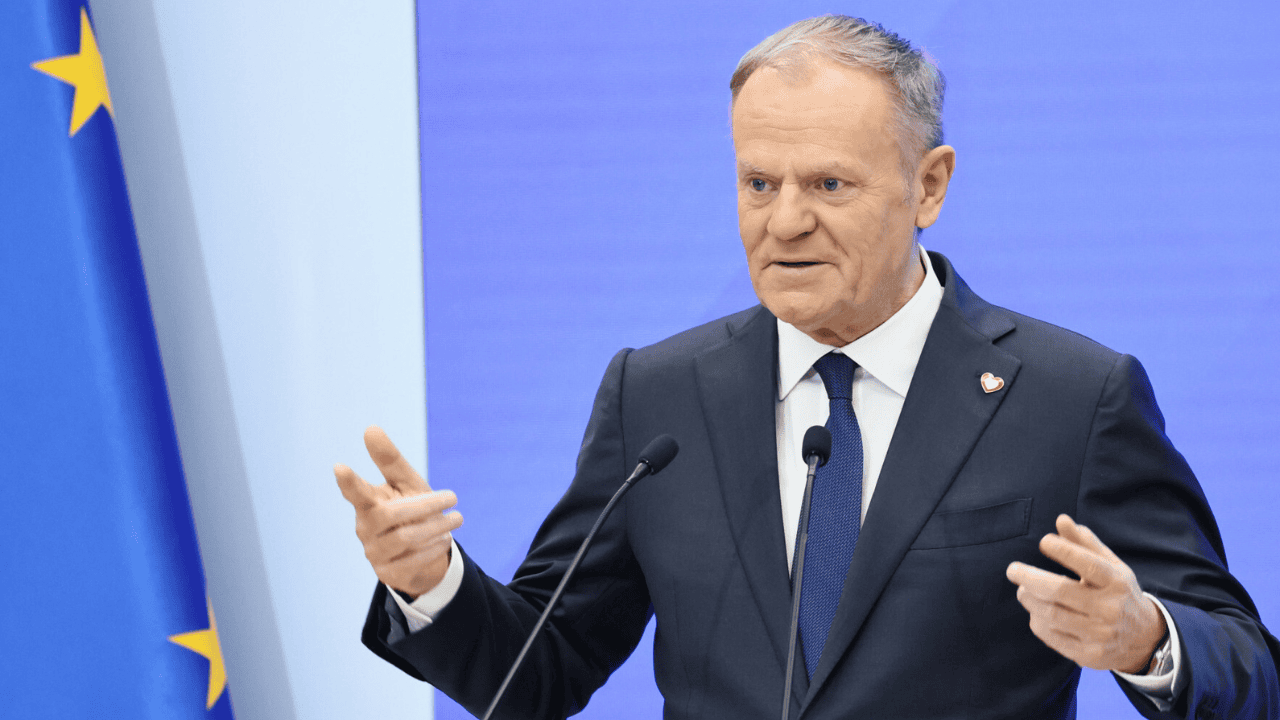

As of 2024, all Baltic Sea nation but Russia is simply a NATO member. In consequence to escalating hybrid attacks, leaders of the region’s 8 NATO nations announced a set of safety measures, including Operation Baltic Sentry, at the Baltic Allies Summit in Helsinki on January 14th. These moves are aimed at deterring future sabotage.

“Since the beginning of June, we have inspected more than 300 tankers and boarded 7 of them,” Estonian Prime Minister Kristen Michal said at the summit’s press conference.

As part of Operation Baltic Sentry, frigates, maritime patrol aircraft and a fleet of tiny naval drones will be deployed.

On the Jotvingis, the usage of 1 specified naval drone is crucial for inspecting underwater infrastructure. “It can descend 55 metres,” the commander explains, standing beside a launch boat. “Then, utilizing a sonar system, it scans the cables, transmitting their condition over a circumstantial area.” erstwhile in the water, the torpedo-like device is controlled through a smartphone app. That day, no harm was detected on the cables 50 metres below the vessel.

The drone is equipped with a sonar capable of scanning an area of 250,000 square metres. Photo: Théo Prouvost

In any cases, the Jotvingis straight monitors the shadow fleet, though it does not intercept vessels. Admiral Premeneckas explains the procedure: “We track them on radar, then conduct a visual inspection at sea. We question the captain and transmit all information to the authorities.”

These authorities are NATO command centres. NATO and the EU have compiled a list of vessels suspected of operating under the Kremlin’s control. “It’s a peculiar list, shared by the European Union and NATO associate states: the “Shadow Fleet” list. all inspection involves checking if the vessel is included,” the admiral explains. Currently, “nearly a hundred” ships appear on this list, though many more are believed to be part of the shadow fleet.

Hybrid warfare

Hybrid warfare, as primarily conducted by Russia against the West, blends conventional military tactics with cyberattacks, disinformation, economical force and covert sabotage. Mark Galeotti, a specialist in Russian safety affairs, has described it as “political warfare utilizing all means short of open war”.

Dressed in his highest naval uniform, Admiral Premeneckas besides notes the environmental risks posed by the outdated, poorly insured and barely maintained ships of Russia’s shadow fleet. “The Baltic is simply a confined sea, meaning a major oil spill could origin an environmental catastrophe,” he says.

Captain Arunas supervises the 50 soldiers aboard the Jotvingis. Photo: Théodore Donguy

On January 12th, 3 German rescue vessels escorted the Eventin, carrying 99,000 tons of crude oil, to prevent a spill. Following the incident, the German abroad Minister Annalena Baerbock slammed Russia for “endangering European safety not only with its war of aggression against Ukraine but besides with decrepit tankers”.

Between 2022 and late 2024, nearly 60 hybrid attacks attributed to Russian intelligence agencies, primarily the GRU and FSB, targeted Europe. The chosen tactics of these actions ranged from physical sabotage to cyberattacks and election interference.

“With these operations, Russia is escalating its hybrid war in Europe, conducting attacks on an ever-shifting front,” said Charlie Edwards, a elder fellow at the global Institute for strategical Studies in London. That day on the Jotvingis, no shadow fleet vessels were detected. But Captain Arunas remains steadfast. “Every Russian operation will receive a consequence from us,” he says.

Théodore Donguy is an independent writer based in Paris. He covers human rights and war in east Europe. He has been published in European outlets including VoxEurop, Paris Match, Hampshire Chronicle and France 24.

Please support New east Europe's crowdfunding campaign. Donate by clicking on the button below.