According to the police report, the tragedy occurred at around 2:30 in the morning on Saturday, October 25th in Novo Mesto, in front of 1 of the bars. According to publically available information, a boy called his father to come and choice him up due to the fact that the people gathered in the bar were threatening him. erstwhile the father arrived at the scene, a group of young men belonging to the Roma community had gathered in front of the bar and intimidated his son.

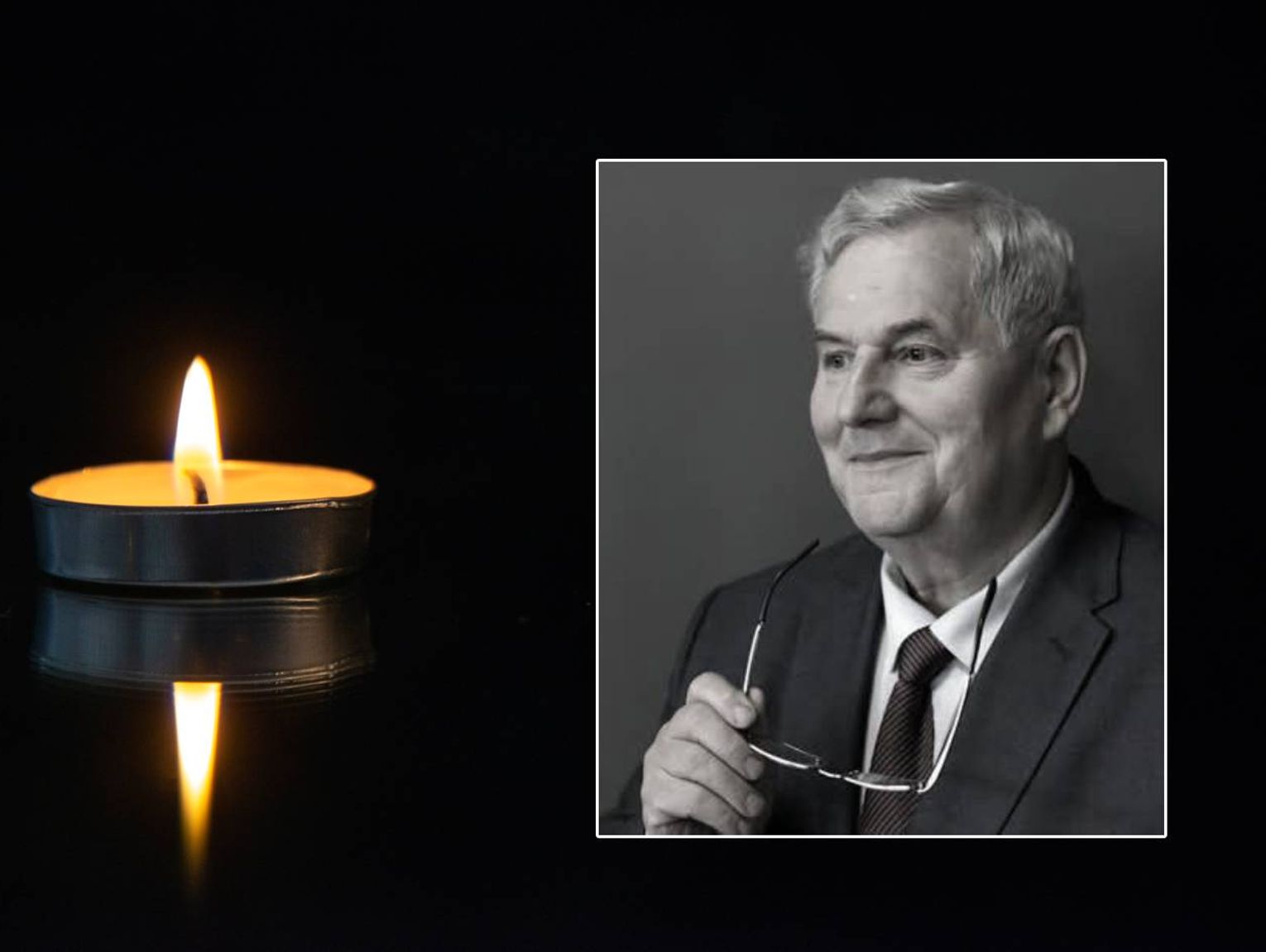

The father intervened and a fight broke out, during which a 21-year-old from the group dealt him a fatal blow. Aleš Šutar died on the following Sunday from his injuries. He was an active associate of the local community.

The police and investigators secured evidence and launched an intensive investigation into the crime. A 21-year-old fishy was identified and arrested on Sunday afternoon. The investigation is inactive ongoing.

According to Mayor Gregor Macedoni, the police had intervened at the premises earlier that night due to violent incidents involving the same group.

In tribute to the victim, a candle light vigil was held on Sunday in front of the premises where the tragedy took place.

The tragedy has shaken Slovenian society beyond Novo Mesto and the region of Lower Carniola. It has highlighted many deep divisions, both social and political, erstwhile more.

Reaction from politicians

Prime Minister Robert Golob called a crisis gathering at which he announced that following the tragic events in Novo Mesto there would be respective resignations. The Justice Minister Andreja Katič and Interior Minister Boštjan Poklukar left their posts, while the Secretary of State for National safety Vojko Volk announced that police officers would further strengthen their presence in the area. If necessary, peculiar police units would besides be sent to the scene. This comment referred to many rumours of possible pogroms and vigilante justice, which had been discussed on social media.

The authorities of the municipality of Novo Mesto have warned that the problem of Roma integration in this part of the country has been worsening for a long time and may now escalate or even culminate, which is why they have called on residents to participate in a protest for greater safety in the local community. The protest march took place on October 28th at Glavni trg, a square in the city centre. This coincided with an extraordinary city council gathering devoted to safety issues in the city.

“This brutal incidental shows that the problem of Roma integration, which has long been highlighted by mayors in south-eastern Slovenia, is clearly worsening, and the state, as the only authority competent to resolve it, is not taking any action despite the seriousness of the situation,” the municipality said in a statement.

According to Mayor Macedoni, government representatives, Ministry of Justice officials, and the judiciary should realize that “too much protection is given to the guilty, and besides small attention is paid to the safety of the innocent.” “In the meantime, while the applicable authorities are looking for solutions, there are besides many real victims with permanent physical injuries and post-traumatic stress disorders in south-eastern Slovenia,” he warns.

“We are facing a real deterioration in the safety situation in our part of the country, and citizens rightly anticipate active and fair action from the competent authorities, who will do everything essential to guarantee our safety, regardless of the cultural group to which the perpetrators of the crimes belong,” he wrote in a statement.

The now erstwhile Minister of the Interior Boštjan Poklukar and Police manager General Damjan Petrič powerfully condemned the brutal attack in Novo Mesto.

As Petrič said in a comment for tv 24ur, the police have been intensively performing additional tasks in south-eastern Slovenia for over a year in connection with the pressing problems in the Roma communities. These are being carried out through an increased presence of all police forces, both in Novo Mesto and another regions of Slovenia. In his opinion, there are “enough” police officers in the field, “but it must be said that it is hard to prevent all crimes, especially if there were no prior indications that would point to this,” he said.

He emphasized that all the most serious crimes involving injury and failure of life in south-eastern Slovenia had been investigated, which means that the perpetrators had been identified and most of them had besides been brought before an investigating judge. He confirmed that the 21-year-old perpetrator who fatally attacked Aleš Šutar had already been punished as a insignificant and had received court sentences for individual crimes involving violence. He admitted that the safety situation in south-eastern Slovenia had not been unchangeable for over a year and that they inactive faced major challenges in this area.

After this tragic event, there were besides many calls for politicians to take work for this tragedy and the general situation in the region.

One of the first to call on the government to take work was the erstwhile associate of the European Parliament Klemen Grošelj, who wrote on social media that the Interior Minister Boštjan Poklukar was objectively liable for this act and called for his resignation.

Numerous political commentators point to the deterioration of the safety situation in the south-eastern part of the country, which they believe is the consequence of the government’s failure to address Roma issues. Integration experts emphasize that they have repeatedly pointed out the request for action and proposed changes to legislation, something that both the current and erstwhile governments have stalled on.

Janez Janša, the leader of the largest opposition party, SDS, besides spoke on the matter. He wrote that his organization would request an extraordinary session of the National Assembly. He called for “the immediate adoption of 4 laws concerning the Roma, which were proposed by mayors and 30,000 voters from the Lower Carniola region, the adoption of measures to destruct double standards in the treatment of crimes committed by Roma, and the prosecution of all those who have so far buried their heads in the sand.”

The changes in question deal with social policy towards Roma, the labour market, driving licences, and education, which, according to eleven mayors from the confederate regions of Slovenia — Lower Carniola and White Carniola — would solve the existing problems there with regards to Roma integration.

Janša added on the X portal that “on the day of the extraordinary session, we gathered for a protest in front of the parliament to support the SDS and NSi MPs in their efforts to convince the leftists, who had previously blocked the essential effective measures, to yet agree to them.” He besides called for the immediate resignation of Prime Minister Golob.

Golob responded on X by saying that “my resignation will not bring the [murdered] father back to his family. The ministers have taken responsibility. My resignation would be evading responsibility, and I do not intend to do so, but I will do my utmost to make life safer in the future, not only in Lower Carniola but throughout Slovenia.”

The leader of the opposition Democratic organization (Demokrati), Anže Logar, besides spoke, announcing that “we have reached a turning point” and “the time has come to call early elections.”

Like Janez Janša, the president of Slovenia, Nataša Pirc Musar, besides called for an extraordinary session of the National Assembly, which, in her opinion, should focus on “a substantive debate with expert arguments and proposals that will enable the essential measures to be adopted more quickly.” The president besides believes that legislative changes are necessary.

All these statements clearly indicate that the tragedy in Novo Mesto has become a pretext for politicians of various persuasions to resume the intense political conflict that has characterized the Slovenian political scene in fresh years, with the deepening polarization of society happening in the background.

In the current situation, analysts point primarily to an increased chance of Janez Janša and his SDS returning to power in the upcoming parliamentary elections, which are to take place at the end of April 2026.

In the debate that has erupted with specified emotion, it is easy to see that while the right wing emphasizes primarily safety issues and the request to integrate individual groups of the Roma community, the left wing, on the another hand, powerfully emphasizes the allegedly racist nature of these statements.

For example, Miha Kordiš, a far-left politician known, among another things, as a staunch opponent of Slovenia’s NATO membership, emphasized that “the political actions and rhetoric that followed the tragedy in Novo Mesto are not honest, and they are surely not aimed at ensuring the safety of citizens (as these are the same people who are dragging us into war with Russia and financing Israel). They are simply a cynical, venomous political calculation, in which it was decided to fuel xenophobia and exploit racism. The pace is set by the far right, the government adapts to it, and a full group of people becomes the mark of a pogrom. Guilty, innocent, it doesn’t matter, let’s just destruct them due to the fact that they are Gypsies.”

Mono-ethnicity, izbris, and the problem of integrating newcomers from the south

On the eve of independence, Slovenia was the most mono-ethnic republic of Yugoslavia, which besides allowed Ljubljana to leave the Socialist national Republic of Yugoslavia comparatively bloodlessly (following the alleged Ten-Day War) during the authoritarian regulation of Slobodan Milošević in Belgrade. The Yugoslav leader then plunged Croatia and Bosnia into the chaos of brutal wars. From the beginning of Slovenian independence, the problem of the alleged izbris (Slovene for “deletion,” “erasure”) casted a shadow over the democratic changes and the building of the structures of an independent state. By virtue of an administrative decision of the first independent government of Igor Bavčar, any residents did not automatically get citizenship of the Republic of Slovenia and, remaining in the registry of another republics of Yugoslavia, lost their right of residence in Slovenia. This was due to a deficiency of appropriate communication from the applicable authorities, so these people did not apply for it. This problem could have affected as many as 20,000 people, whose life choices in individual situations were very difficult, especially erstwhile they were facing deportation to war-torn Croatia or Bosnia.

For more than 2 decades, Slovenia has been a country of mass immigration, mostly from the countries of erstwhile Yugoslavia, especially Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbia and Montenegro. A importantly higher standard of surviving and at least 3 times higher wages, as well as political and social stability, comparative linguistic proximity, and efficient administration (compared to their home countries) encourage many citizens to emigrate for work or to resettle permanently in Slovenia.

For many years, it was believed that most of these people would either assimilate “automatically” or return home erstwhile they had made their fortune. The comparative similarity between the languages spoken by the newcomers and Slovenian suggested that specified assimilation was theoretically possible. This never full materialized, but over the erstwhile decade, a fresh wave of migrants has arrived in Slovenia – cultural Albanians from Kosovo and North Macedonia who talk neither Slovenian nor any another Slavic language. Until Kosovo citizens were granted visa-free travel to the Schengen area in 2024, the Slovenian consulate in Pristina was 1 of the leading consulates in the full region in terms of issuing visas among all Schengen countries.

As a result, the increasingly pressing issue of integrating these people into Slovenian society has yet begun to be noticed. This is especially actual in education, where until now there have been no integration programmes for children who talk neither Slovenian nor any another South Slavic language. In addition, in fresh years, there has been an influx of Ukrainian refugees due to the Russian full-scale invasion of their country. At the same time, many Russians chose Slovenia even before the war broke out as a safe country for relocating their capital and surviving peacefully in the West, close to Austria and Italy. The same is actual of many wealthy Serbs, Bosnians and Macedonians, for whom Slovenia was and inactive is simply a substitute for the close and “familiar” West.

Over the past 5 years, immigrants from outside Europe have besides begun to arrive in Slovenia, mostly citizens of India, but besides Bangladesh, the Philippines, China and Turkey among others.

However, in all this, attempts have been made to ignore the problem of the integration of Roma, who are citizens of Slovenia. Usually, erstwhile talking about Roma in Slovenia (if at all), the focus was on Prekmurje, a region in the east of the country on the border with Hungary, which was cited as an example of the successful integration of this community. At the same time, the situation in the south, in White Carniola and Lower Carniola, where this community is much larger and the integration process is far little successful than in Prekmurje, was ignored.

“In Slovenia, the general regulation is that assimilation is not imposed by law,” a friend from the University of Maribor tells me. “That is why we have 50,000 Bosnians who have been here for 30 years, but most of them inactive don’t know the Slovenian language. Or 150,000 Albanians from Kosovo and Macedonia who know neither Slovenian nor English and form virtually closed, hermetic communities.”

As for the Lower Carniola region, the situation is exacerbated by the fact that it is simply a comparatively sparsely populated part of the country, home to little than 10 per cent of Slovenia’s population, while the only major employer is the Krka pharmaceutical concern in Novo Mesto. Conflicts between the Roma and cultural Slovene communities in small, scattered towns are plain to see.

Is it the responsibility of the state or the municipalities?

Statistics clearly show that where local municipalities act systematically and consistently, the situation is orderly. Where, on the another hand, the problem is solved on an ad hoc basis or swept under the carpet, full generations are caught in a vicious circle.

The problem of coexistence between the Roma community and the majority population is not new. The origin of contemporary tensions dates back to the 1990s, and the aforementioned “izbris” divided Slovenia (to this day) into 2 camps: ‘integration’ versus “expulsion”. Since then, the south of the country (Lower Carniola, White Carniola, interior Carniola) has been caught in a vicious cycle of “security incident, political pressure, firefighting measures, silence, and then a fresh outbreak”.

Over the course of 20 years, respective governments have changed laws, and circumstantial legal and administrative mechanisms have besides been adopted. Among them is:

– National Action Program for Roma for 2017–2021 and 2021–2030;

– strategy for the Education and Upbringing of Roma;

– many reports by the Human Rights Ombudsman accurately describing the situation;

– State projects concerning the improvement of settlements, infrastructure, the activities of mediators, education, and employment;

These measures covered most municipalities in Slovenia, including Prekmurje.

However, in the municipalities of Novo Mesto, Ribnica, Šentjernej, Črnomelj, Kočevje, Metlika, Trebnje, and another localities, the other model has emerged:

– deficiency of fresh long-term strategies;

– most programmes after 2021 have not been extended;

– disorderly settlements without infrastructure;

– deficiency of ongoing dialog between communities;

– the police are blamed first, followed by the current government.

The attitude has been adopted that erstwhile things are calm, municipalities usually do not intervene, but erstwhile an incidental occurs, “the state must solve the problem.”

In summary, where municipalities are active, coexistence functions properly. Where municipalities neglect to take appropriate action, the government is seen as a tool for putting out fires.

The tragedy in Novo Mesto has only highlighted a long-standing problem, while at the same time provided an excellent platform for various populists – from the right to the left – to prosecute their short and long-term goals in the face of the upcoming parliamentary elections.

Nikodem Szczygłowski is simply a reporter, author and translator from Lithuanian and Slovenian. He is simply a frequent contributor with New east Europe as well as another media outlets.

New east Europe is simply a reader supported publication. delight support us and aid us scope our goal of $10,000! We are nearly there. Donate by clicking on the button below.